Week 5 - Thread design Considerations

Additional reading

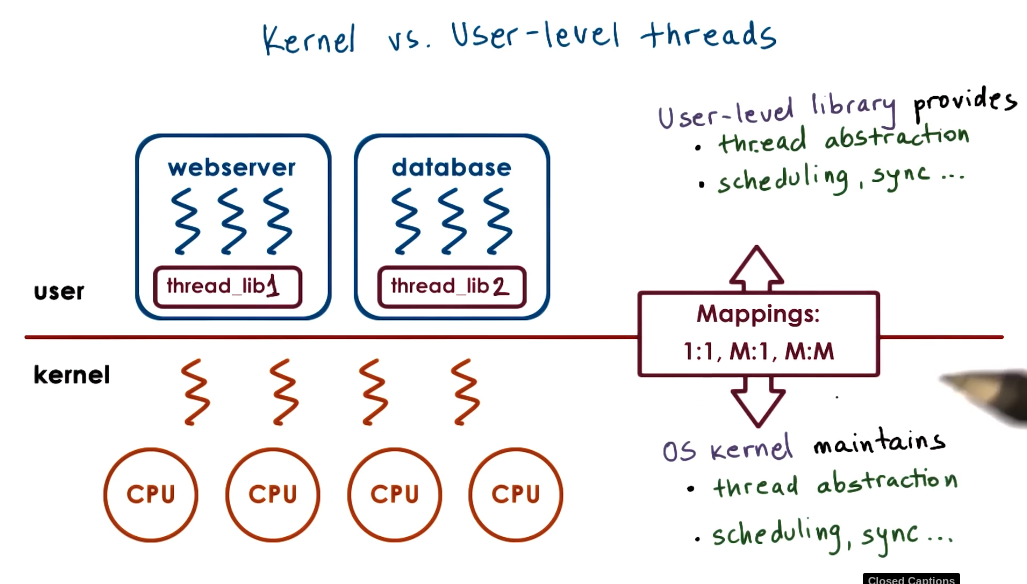

Thread level

We will be revisiting the thread level from Thread level.

Key summary:

- Kernel level threads get scheduled on the CPU.

- User level threads get mapped to kernel level threads - this is decided by the user threading library.

- These are functionally just an abstraction to assist application development.

Thread data structures

In previous lecturers we spoke about a Process control block (PCB) as a single entity. However, when adding threads into the equation it is more convent to break this down into the bit.

- The hard state that is shared by all threads - like the memory mapping,

- the soft state that is shared by some threads like how to handle signals and system calls, and

- the thread specific state like its current stack and registers.

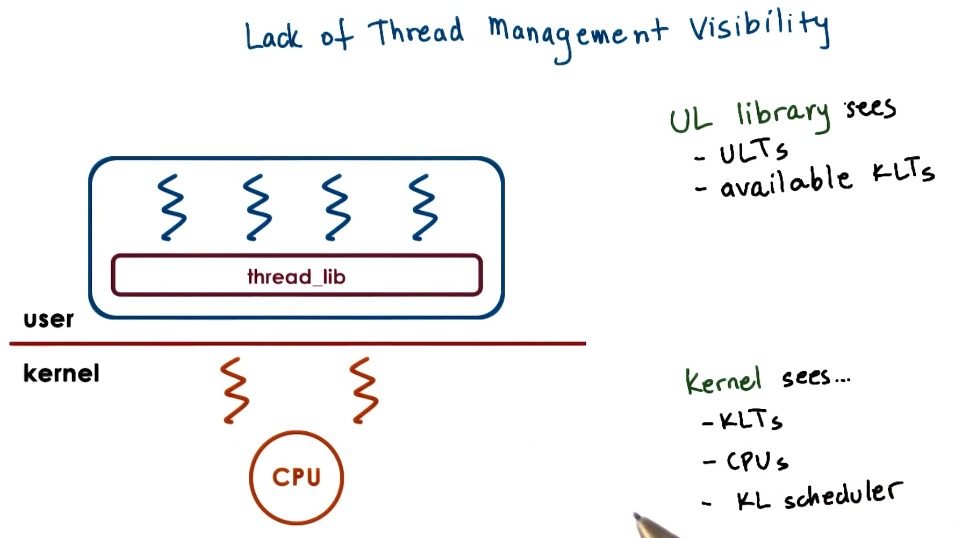

As we discussed previously the threading library (which can be different for each process) controls the mapping between the user threads and the kernel threads. The kernel threads are the ‘real’ threads from the perspective of the CPU - these get scheduled onto the CPU. The user threads are not known by the CPU, it is the responsibility of the threading library to map these onto the kernel threads to be executed. This can be done in multiple relationships that have upsides and downsides.

- Many user threads to one kernel threads. This was mainly used by old programming languages, whilst allowing for some parallelism if one threads is mapped onto the kernel thread and uses an I/O operation it blocks all user threads.

- 1:1, common in modern programming languages like pthreads in c. Allows for the most parallelism but decreases portability as it demands a lot of resources from the system it is running on and increases the amount of overhead as it needs a kernel operation to switch user level threads.

- Many to many, balance between both - allows for parallelism whilst also making optimizations to not need so many context switches. Used in programming languages like go.

The process control block go broken down into small components to increase:

- Scalability,

- Reduce overheads,

- Increase performance, and

- Make the system more flexible.

In a single PCB we have:

- Large continuous data structure - decreasing scalability.

- This is private for each entity such as thread - which increases overheads.

- This needs to be saved and restored on each context swich - decreasing performance.

- Would need to update the whole data structure for any change - making the structure less flexible.

With the broken down state we:

- Have smaller data structures - increasing scalability.

- They are easier to share and reference - decreasing overheads.

- Context switches can update only what has changed - increasing performance.

- Updates can be carried out on one component - making it more flexible.

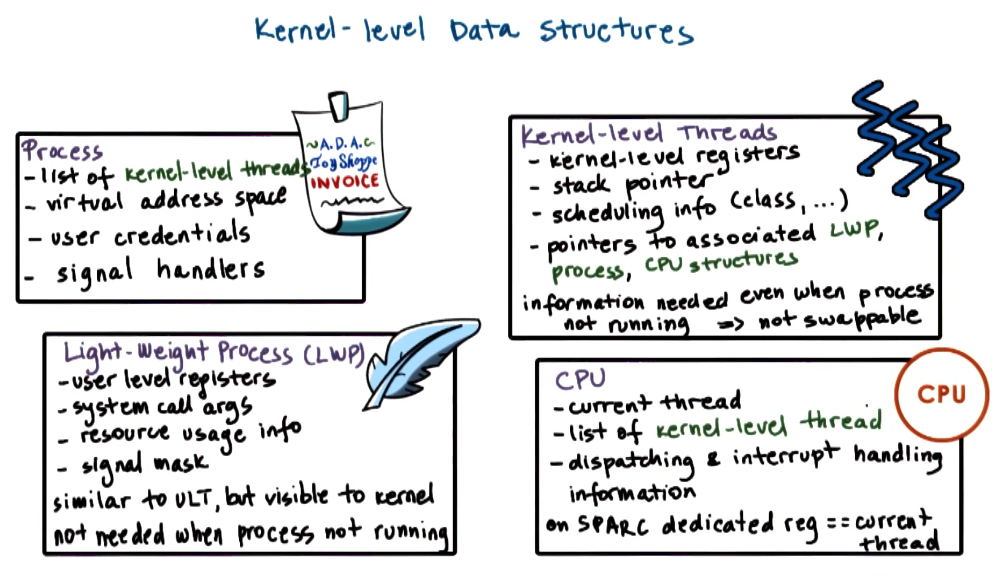

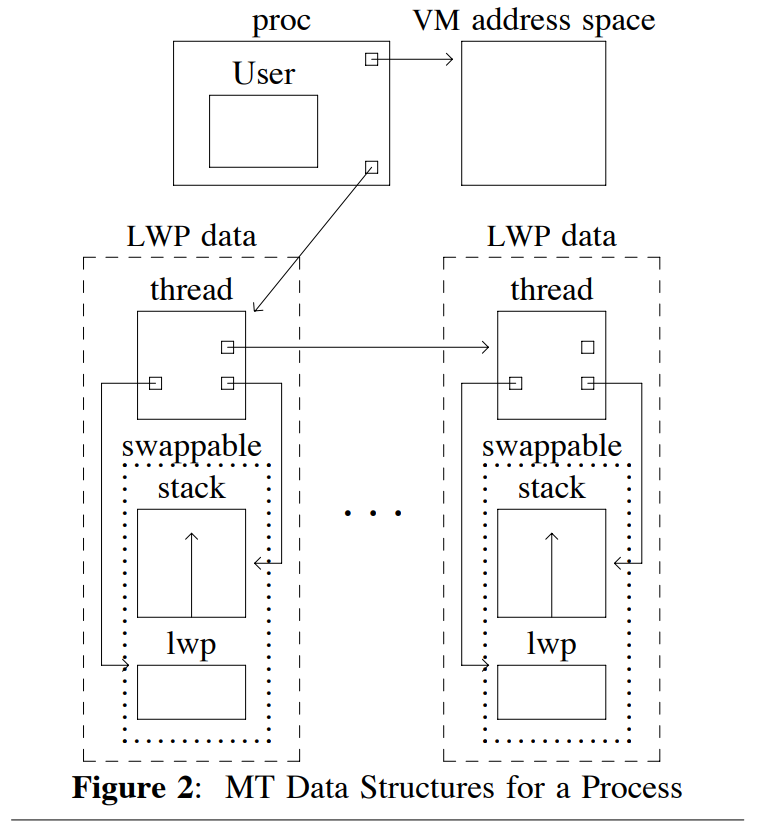

SunOS 5.0

This OS implements Light Weight Process as laid out in Week 5 - Beyond Multiprocessing … Multithreading and the SunOS Kernel. The data structures to implement this are laid out in Week 5 - Implementing Lightweight Threads (paper).

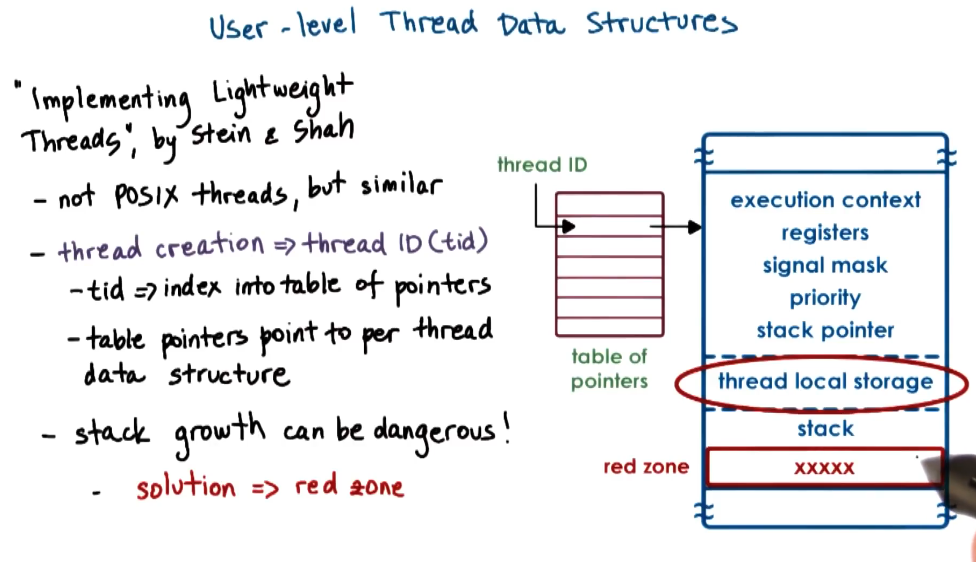

User level structures

Two key points:

- Threads point to their ID within a table of pointers - this enables that table to contain metadata about the thread and stops it pointing to corrupt memory.

- The stack for each thread can grow beyond the bounds of the initial allocated stack size. If this happens it would corrupt another thread but it would not be known until that thread ran. To mitigate this they implement red zones which if edited will throw a seg fault.

Kernel level structures

Key notes:

- Resource usage is tracked per LWP this means to get the resource usage for a kernel-level thread, we need to traverse the linked list of LWP.

- The kernel-level thread always has to be loaded in memory for access however the LWP does not. This allows for larger LWP support with a lower memory foot print.

Thread management

The kernel level does not understand what is happening at the user level and vice versa. Therefore we can get into situations where all kernel level threads are blocked on I/O whilst there are user level threads that could execute. Therefore SunOS introduce new system calls to allow the kernel level threads to communicate to the threading library.

Notes:

- It is possible for threading library to lock a user level thread onto a kernel level thread.

- There are situations where when the kernel doesn’t know about mutexs or conditional variables, the user level threads are blocked by the kernel without it knowing.

- The threading library gets called at different points such as: Via signals, ULT yielding, blocked threads becoming runnable, or timers expiring.

Multiple CPU ‘fun’

There are situations where actions on one CPU effect another, such as:

- With 3 threads

and 2 CPUs. If holds a mutex needs then and are scheduled. When releases the mutex it needs to signal to to run the threading library to switch for . This is called preempting . - This is enabled by

signaling .

- This is enabled by

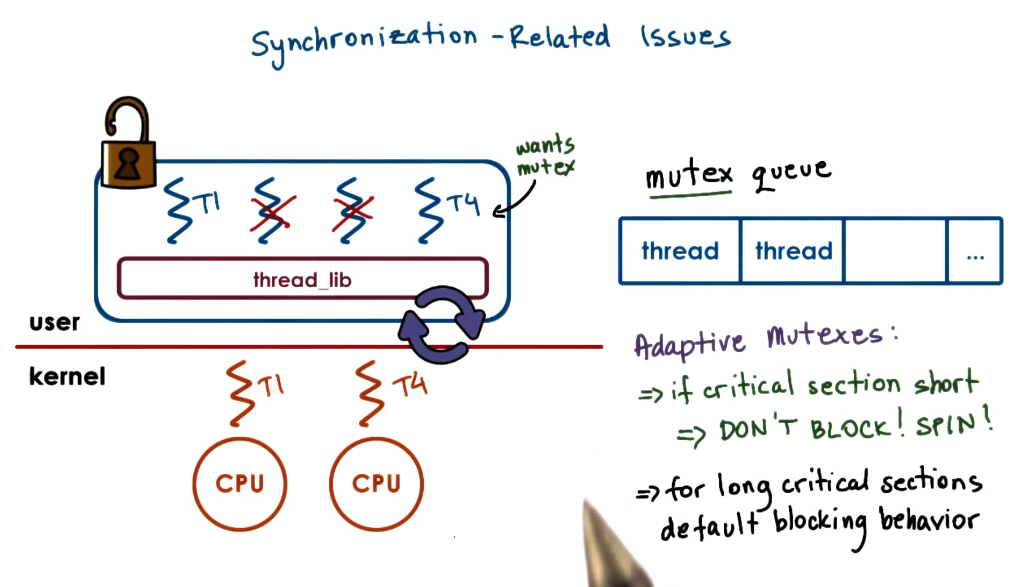

- In the case where 2 threads are running on two CPU’s

and (see picture) it may be the case where needs a mutex is holding. If the critical section of is short it may be faster for to stay loaded on the CPU than to context switch out. This case is called an adaptive mutex.

Creation of threads takes a while so instead of destroying them it is efficient to reuse them. Therefore when a thread is marked for distruction:

- It is put on ‘death row’

- periodically a reaper thread destroys unused threads.

- Otherwise when a new create call is made it reuses an old thread structure.

Interrupts and signals

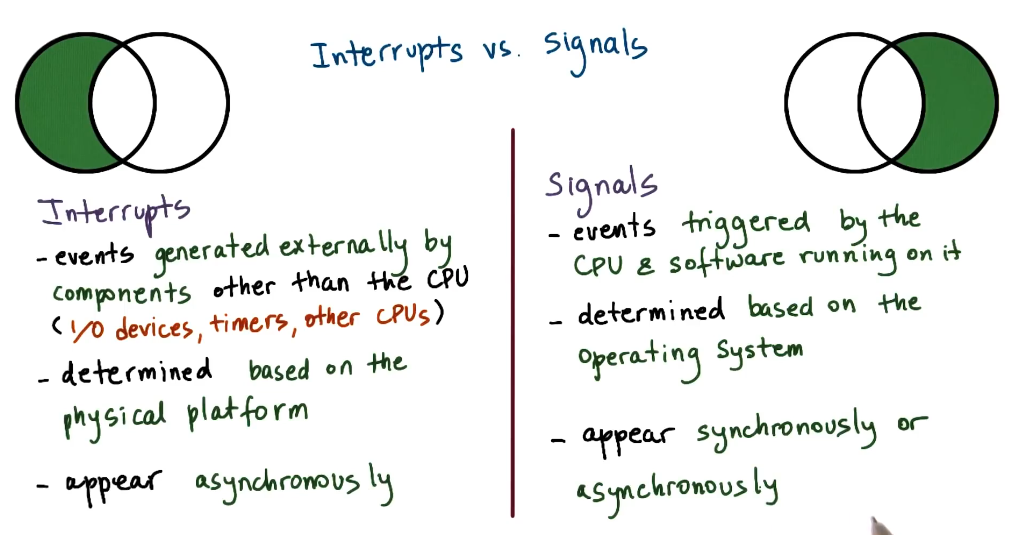

Interrupts

- Interrupts are caused by hardware devices.

- The OS defines a handler table going from the interrupt to the address of the handling code.

- When the interrupt is given if it is NOT masked then the current thread’s execution counter is moved to the handling code.

- This is all defined in the OS and can not be remapped by the process.

- Interrupts are always asynchronous.

Signals

- Signals are caused by the CPU/process - such as accessing memory not allocated to it.

- The OS defines a handler table mapping signals to the address of the handling code.

- The process can change the address of some of these handlers.

- When the signal is given if it is NOT masked then the current thread’s execution counter is moved to the handling code.

- Signals are defined by the OS.

- Signals are either synchronous or asynchronous.

- Synchronous: Segmenation fault, dividing by 0, or sigkill sent from one thread to another.

- Asynchronous: Sigkill from outside or sigalarm.

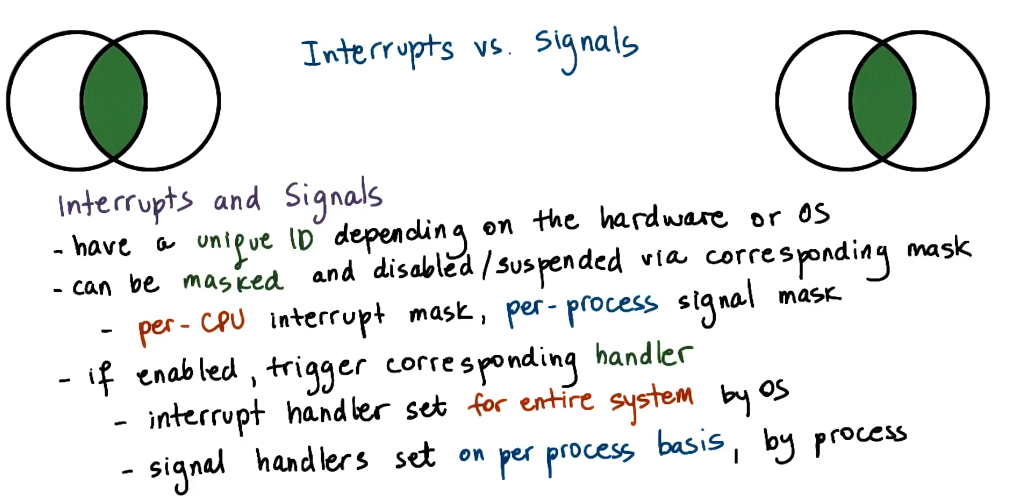

Masking

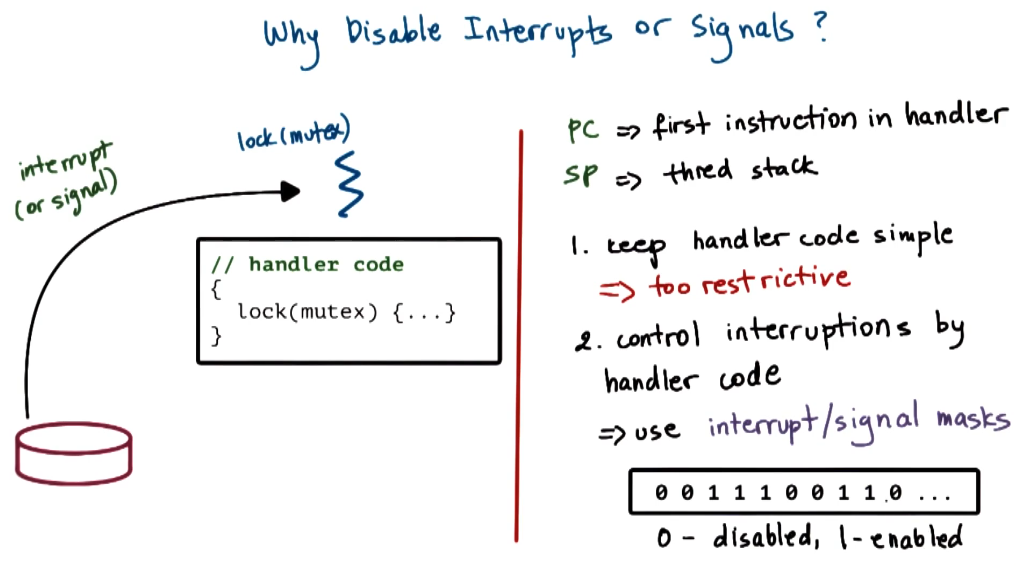

Switching immediately to handler code for either signals or interrupts can cause code to become incredibly complicated. For example if the code that is interrupted is holding a mutex, but the handler code needs another mutex it risks deadlocks within your system.

The solution to this is to mask (i.e. block) certain signals/interrupts from happening around critical sections to stop this happening. Signals/interrupts when blocked get queued up.

Interupt masks are per CPU. If a mask disables the interrupt, the hardware interrupt routing mechanism will not deliver interrupts to that CPU.

On a multi-core system the interrupt is handled by whichever CPU has that interrupt unmasked. It is common practice to have a single core unmask the interrupts and be the main handler. This avoids overheads and instability on the other cores.

Signal masks are per execution context. If the mask disables a signal, kernal sees the mask and will not interrupt the corresponding thread.

There are two types of signals:

- One-shot signals: If multiple signals are queued it is only guaranteed to run the handler at least once. Also user specific handlers must be re-enabled after execution otherwise we default back to the OS’s handler.

- Real time signals: If n signals are raised then the handler is called n times.

Threads handling interrupts

One way to get around deadlocks within interrupt handling is to spin the thread handler out in its own thread. That way if the handler gets blocked on a mutex it can context switch back to the interrupted thread to finish before it can finish execution.

The main downside to this is dynamic thread creation is quite costly. Therefore there is optimizations here to be made:

- If the handler does not lock, it can be executed on the original thread.

- If the handler does lock, then make it a separate thread.

- Create and initialize threads for interrupt routines before they are called.

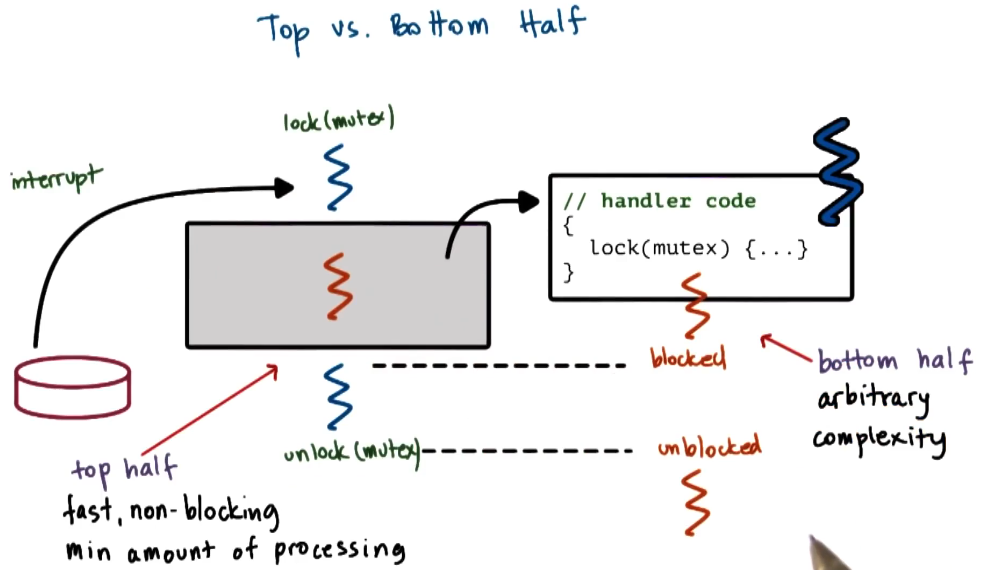

There is a concept of top and bottom of the thread handler.

- The top is the part that executes within the interupted thread.

- The bottom is the part that executes within the spun out thread.

- In the bottom we can enable interupts that were disabled in the top - as it should be safe here to handle other signals.

If we use a new thread instead of blocking signals whilst in the critical section we have the following changes:

- It adds about 40 instructions per interrupt, and

- It saves about 12 instructions per mutex opeation.

Optimize for the common case

As there are fewer interrupts than mutex operations this causes a net saving.

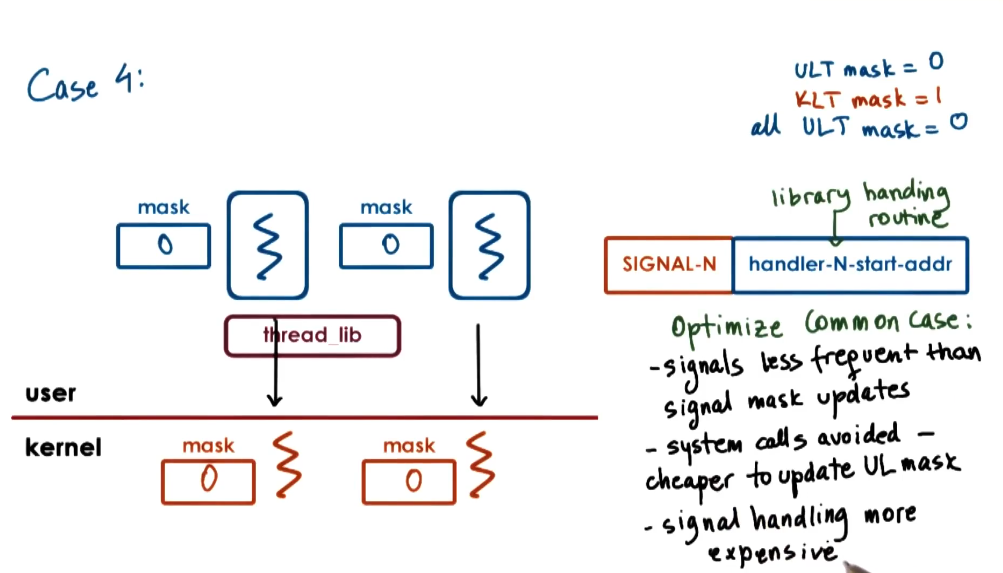

User vs kernel masks

Both the kernel level thread and the user level thread have signal masks. For the user level thread to update the kernel level threads mask this takes a system call - which is slow. So these are kept in sync via lazy updates.

The threading library loads its own code into the signal handler for a particular signal. Then there are multiple cases on what should happen.

- Case 1: Both user and kernel threads have mask set to 1, threading library lets the user level thread handle the signal.

- Case 2: Kernel thread has the mask set to 1, but the current executing thread has it set to 0. However there is a non-executing thread with the handler set to 1 - so we context switch.

- Case 3: Kernel thread has the mask set to 1, but the current executing thread has it set to 0. However there is an executing thread with the handler set to 1 - so this thread passes the signal onto the kernel level thread executing that user level thread.

- Case 4: Kernel thread has the mask set to 1, but the current executing thread has it set to 0. All other user level threads have the mask set to 0. We invoke a system call to set the kernel level mask to 0 and throw the same signal in another executing thread.

- Case 5: All kernel threads have the mask set to 0 and the user level thread switches its mask to 1. Then we make a system call to switch the mask to 1 on this kernel level thread.

Linux

In linux it supports the Native POSIX Threads library (NPTL):

- This is a 1:1 model so avoids the complexity on the many:many model in SunOS.

- Kernel sees each user level thread.

- Kernel traps are cheaper in linux.

- More resource so limitations like the number of threads matter less.

Linux used to use LinuxThreads a many:many model similar to SunOS above.

In linux it calls the thread IDs PID (process ID’s) which is mildly confusing. All the threads have a group ID which is the PID of the first thread. When you fork a process it only copies the first thread. To create a new thread us use clone with a mask that indicates how much you want to copy over.