Week 1 - Writing and reading papers

Ten simple rules for reading a scientific paper by Maureen A. CareyID, Kevin L. Steiner, William A. Petri Jr

Reading articles is a large part of research and you should try to keep up to date with your area of interest. However, may people struggle with reading articles and this guide is some tips and tricks for starting.

Rule 1: Pick your reading goal

Understand why you want to read this paper, and set your priority straight from the beginning so you don’t get lost in the forest of knowledge.

Rule 2: Understand the author’s goal

You may be able to work this out from the introduction. Though try to take into account other publication titles of that author. Ask questions like is this paper in the authors field? Are they working towards a bigger goal? What are their scientific interests? This is hard at first but as you get more a custom to an area gets easier.

A good first step to understand the type of article: methods, review, commentary, resources, and research articles.

Rule 3: Ask six questions

For each article ask:

- What do the authors want to know (motivation)?

- What did they do (approach)?

- Why was it done that way (context)?

- What do the results show?

- How was this interpreted?

- What should be done next?

This can be done for each table/figure as well as for the paper as a whole.

Rule 4: Unpack each figure and table

The data is the most important part of the paper - starting with that to understand the words around it can help. For graphs, you should be able to explain all the components, axises, colours, and statistical approach. For each table understand what are the experimental groups, variables presented, and what was calculated vs collected.

Rule 5: Understand the formatting intentions

Understand why the author grouped results into different sections and what the goal of each of them was. This can be helped by understanding the usual roles different bits of the paper are to achieve.

Rule 6: Be critical

Science is a never-ending working in progress

Whilst models have their bias so do do humans and the author may have missed something. We all come with confirmation bias of our own hypothesises.

Always start with the data and see if you agree with their conclusions from that. Are there potential other conclusions that could be drawn.

Rule 7: Be kind

Don’t let poor formatting or incorrect labelling influence your opinions about the quality of the results. People make mistakes.

When talking to colleges about papers try to be kind when it comes to little mistakes and don’t dwell on them.

Rule 8: Be ready to go the extra mile

Some people suggest the read it 3 times approach:

- Read without need to critic or understand anything.

- Aim to understand the paper and what it is saying.

- Take notes and extract information from it.

You may have to chase down references, look up terms and find out supplementary material to understand what is going on. (Though I strongly argue this is a poorly written paper.)

Rule 9: Talk about it

Reading papers with people and talking about them is a great way to get a different perspective on the information. Another option is to talk to other people and try to teach them results in the paper.

To teach is to learn twice

Social media or within your research group has become a great way to learn.

Rule 10: Build on it

The point of reading papers is so you can do more. Think about how to apply methods within a paper to one of your own projects. Or if you can use results from this paper to help you. Science is not a spectator sport.

Ten simple rules for structuring papers by Konrad Kording and Brett Mensh

Being able to write and publish papers is one of the key indicators of success within science. It is worth understanding how to do it well.

When writing a paper you need to understand there are different groups of people involved:

- Editors want to make sure that the paper is signification,

- Reviewers want to determine if the conclusions are valid,

- Readers want to quickly understand the conceptual conclusions before deciding if they want to read the paper, and

- Writers want to attract the broadest possible reader base.

The learning rate of new information is one of the biggest limitation to the growth of scientific knowledge. It is helped a lot by the interconnection of common ideas, understanding how your area applies to the bigger picture.

The first place to start is to make the logic of your paper as clear as possible. With all assumptions and reasons for conclusions transparent.

Rule 1: Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

(Much like in programming, you can use this principle in papers at all levels.)

Do one thing in a paper and convey that in the title. Titles are the most read component of any paper so it should be clear and concise what this is achieving.

Write the title of the paper early and use it reground you on any decisions about whether you need to include something in the paper.

By adding more conclusions to a paper, you decrease its over all perceived value. Similar to the broken tea cup analogy.

Rule 2: Write for a laymen

You are the world leading expert on what you are trying to get across. You will assume people know more than they do, so assume you are writing the paper for someone who knows nothing about your area. Also, don’t help the pervasive Imposters syndrome by assuming people know stuff they don’t.

It is also helpful to understand human Psychology so we can write them in a human friendly way and get our point across better. For example start and end point bias means we should focus the most time on opening and closing sections.

Rule 3: Stick to the Context content conclusion (CCC) model

Stories normally are structured with 3 components, a beginning which sets up the story, the middle where the problems are confronted and solve, and an end which ties that story off. This has an analogy in academic writing as well.

Context content conclusion (CCC)

Context content conclusion (CCC)

This is a model to structure writing. The idea is to separate what you are writing into 3 discernible blocks:

- Context: Sufficient background information for people to read the content with purpose. This should include motivation and the set up for the problem.

- Content: The substance to what you want to say and you show your approach to the problem.

- Conclusion: Summarise what you have solved and how.

Remember Start and end point bias!

Advantages

This will provide the reader the full context to understand what you are trying to say and frame it in a way that is memorable.

Disadvantages

This is assuming a patient reader that is happy to understand the context before getting to the point. This should be used when people already have buy in to what you want to say.

Reference

Link to original

This is a useful structure to follow at all levels of the paper, from the overall structure to each paragraph. Whilst it does have the downside of losing impatient readers - outside of the abstract / introduction we can assume the reader is already on board for the ride.

It can be tempting to break the structure for a chronologic record of results or a personal autobiographical comment. Avoiding this is normally best and helps the reader understand the content better.

They (readers) do not care about the chronological path by which you reached a result; they just care about the ultimate claim and the logic supporting it

Rule 4: Organise you logical flow by using Separation of concerns (SoC) and using parallelism

Avoid dipping in an out of a concept constantly revisiting them unless they are the central purpose to your paper. Use the separation of concerns principle to isolate individual ideas to area.

If you address a topic repeatedly - try to do so in a parallel way. Use a single definition for concepts and structure each component similarly. This will make it easier for the reader to digest.

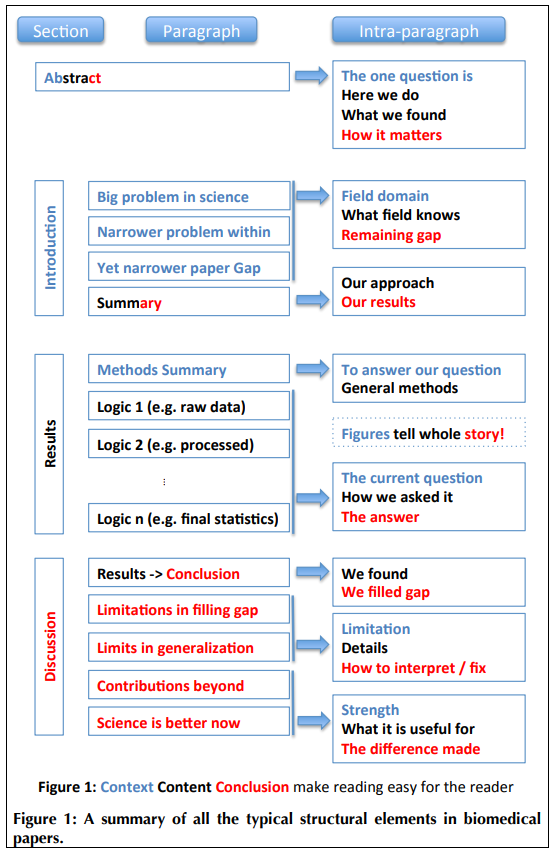

Aside: Typical structure in biomedical papers

Figure 1 from Ten simple rules for structuring papers

Figure 1 from Ten simple rules for structuring papers

Rule 5: Tell a complete story in the abstract

The abstract is the 2nd most read bit of your paper after the title. This should be no more than a paragraph and follow the Context content conclusion (CCC) structure. It should avoid jargon or subtle terms that can be misunderstood to be the most widely understood.

Context - This needs to reflect the current state of the art and distinguish the gap you are filling.

Content - Describe your approach highlighting any new methods you used to fill the gap. Then talk about the results you have gotten.

Conclusion - Interpret the results and show why it fills the gap you presented. Lastly relate this back to the wider field.

Getting the abstract right is very important so may get revised a lot.

Rule 6: Get across why the paper matters in the introduction

You should use paragraphs in the introduction to narrow in on the gap in the current knowledge. Start at the highest level and zoom in slowly. The last paragraph will have its context provided by the previous paragraphs so can start with the lowest level of gap you are fixing.

Rule 7: Results should build on one another to support a central claim

The results section should use data and logic to prove your central claim. Each method may have its own logical structure but keep in mind that everything should be building to prove your central claim. Each paragraph should start with a sentence answering why it is there.

Lots of people don’t read the results section, or skim it. There are two things you can do to assist these people.

- Make the first paragraph a summary of your approach.

- The figures and tables should tell the story without the words.

Rule 8: End with how you filled the gap, limitations to that, and future work

For people who didn’t read the results section, summarise how you have filled the gap in knowledge in the first paragraph.

The following paragraphs should talk about the limitations of your approach but link to the literature on why you choose to do it this way.

Lastly open up your work to be built on, and talk about how your work can be used to further the field.

Rule 9: Focus time where it matters, Title, abstract, figures, and outlining

Starting with an empty page is always hard. It is good to have organised notes that link together and help build the logic of the paper - this is the most important thing in the document.

When it comes to formalising your notes into a paper. Spend time proportional to how much it gets read: Title, abstract, introduction, figures, conclusion.

Doing this is helped by making an outline of the paper to start with bullet points about what goes where. This will define the overall story line and help you bring focus to the bits that matter.

Rule 10: Get feedback to reduce, reuse and recycle the story

Use test readers to understand where the paper falls down. Don’t get attached to what is there and either delete, rewrite or move text to help the flow of the paper. Though, make sure you discern preference verses substance of comments - be critical before just accepting them. Do this graciously as they have put in time to help you.

Writing is an optimisation problem, which takes many iterations and for you to know what you are optimising for.