Week 7 - Software defined networks

Software defined networks (SDN)

Link to originalSoftware defined networks (SDN)

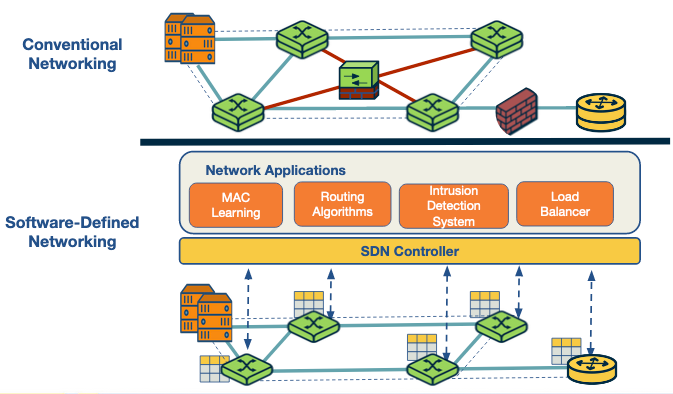

This is a paradigm of networking where you use a remote SDN-controller for the control plane for network devices. This has API’s for communicating with the data plane of the controlled devices but also an outward API to talk to a further management plane. This allows for central control over a whole autonomous system or network.

Additional reading

Important Readings

The Road to SDN: An Intellectual History of Programmable Networks

https://www.sigcomm.org/sites/default/files/ccr/papers/2014/April/0000000-0000012.pdfLinks to an external site.

Book References

Kurose-Ross, 7th Edition. Section 4.1.1

Kurose-Ross, 7th Edition. Chapter 5

Optional Readings

SDN Controllers: Benchmarking & Performance Evaluation

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1902.04491.pdfLinks to an external site.

SDN Architecture

https://www.opennetworking.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/TR_SDN_ARCH_1.0_06062014.pdfLinks to an external site.

Optional Activity

OpenDaylight Application Developer’s Tutorial

History

There was two main factors in the drive to switch to SDNs:

- Diversity of device types: after routers and switches the introduction of middleboxes caused an explosion of devices network mangers had to look after.

- Proprietary Technologies: A lot of the software ran on routers, switches, and middleboxes was closed and configuration interfaces varied between vendors. Therefore we needed to separate tasks up and define a well defined and consistent interface between the control plane and data plane of these devices.

There were 3 main steps in the journey to the definition of an SDN.

1. Active Networks (Mid-1990s to Early 2000s)

Goal: Introduce a programmable network interface (network API) to customise packet handling and innovate network services despite the slow standardisation process by IETF.

Approaches:

- Capsule Model: In-band code carried in data packets.

- Programmable Router/Switch Model: Code carried via out-of-band mechanisms.

Contributions:

- Lowering innovation barriers through programmability.

- Enabling network virtualisation for experimentation.

- Proposing unified control over middleboxes.

Challenges: Too ambitious, requiring end-user programming and facing trust, performance, and security issues.

2. Control and Data Plane Separation (2001 to 2007)

Goal: Improve network reliability, predictability, and performance by separating the control and data planes in response to increasing traffic volumes.

Innovations:

- Open Interface: Between control and data planes.

- Centralised Control: Logically centralised network control.

Contributions:

- Path selection based on traffic load.

- Minimising routing change disruptions.

- Handling attack traffic and enabling customer control.

Challenges: Initial scepticism about separating control and data planes, leading to foundational concepts for OpenFlow API.

3. OpenFlow API and Network Operating Systems (2007 to 2010)

Goal: Facilitate scalable network experimentation and practical deployment through programmable networks.

Innovations:

- OpenFlow Switches: Use tables of packet-handling rules to manage traffic.

Contributions:

- Supported large-scale network experimentation.

- Improved data-centre network traffic management.

- Encouraged investment in control program development over proprietary switches.

Effects:

- Generalised network device functions.

- Introduced the vision of a network operating system.

- Developed distributed state management techniques.

SDN functionality

Separation of Data and Control Plane

There were two main pushes for this:

- Independent evolution and development.

- Control from higher-level software.

This led to developments in many areas such as: Data centres, routing, enterprise networks, and research networks. Through the ability to control the behaviour of all devices through a single centralised point.

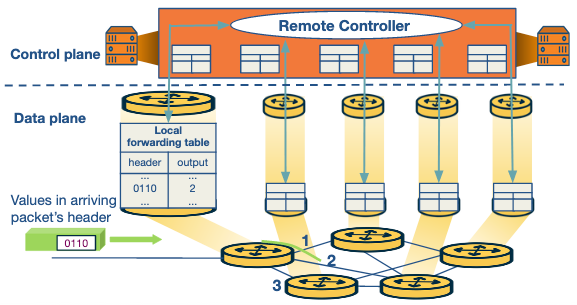

The main role of the data plane is the forwarding of packets based on some FIB, whereas the main role of the control plane is routing which mainly involves updating the FIB once it has computed the route a particular packet should take.

A SDN moves the control plane from being on the device to being located somewhere else on the network. It defines a clean API on how this networked control plane can interact and update the FIB on the device.

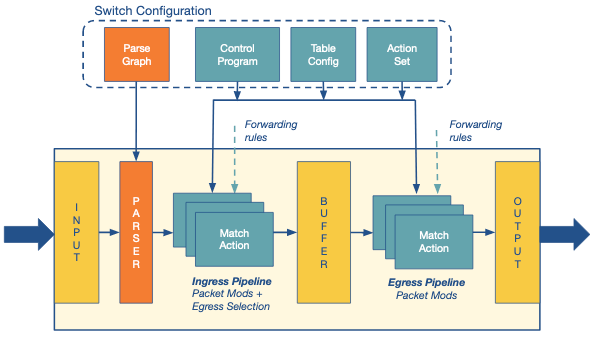

Architecture

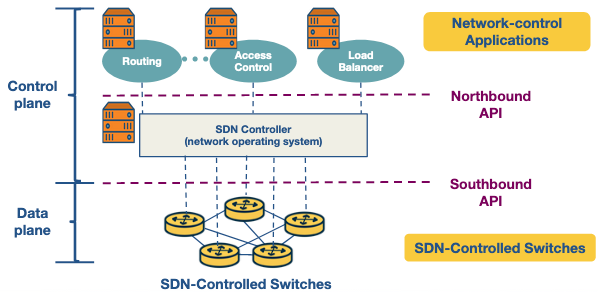

There are 3 separate layers to the architecture:

- SDN-controlled network elements: The SDN-controlled network elements, sometimes called the infrastructure layer, is responsible for the forwarding of traffic in a network based on the rules computed by the SDN control plane.

- SDN controller: The SDN controller is a logically centralized entity that acts as an interface between the network elements and the network-control applications.

- Network-control applications: The network-control applications are programs that manage the underlying network by collecting information about the network elements with the help of SDN controller.

These components have two important interfaces.

- Southbound API: Connecting the SDN controller to the SDN-Controlled switches.

- NorthboundAPI: Allowing other network applications to interface with the SDN controller.

There are 4 important features of this architecture:

- Flow-based forwarding: The rules for forwarding packets in the SDN-controlled switches can be computed based on any number of header field values in various layers such as the transport-layer, network-layer and link-layer. This differs from the traditional approach where only the destination IP address determines the forwarding of a packet. For example, OpenFlow allows up to 11 header field values to be considered.

- Separation of data plane and control plane: The SDN-controlled switches operate on the data plane and they only execute the rules in the flow tables. Those rules are computed, installed, and managed by software that runs on separate servers.

- Network control functions: The SDN control plane, (running on multiple servers for increased performance and availability) consists of two components: the controller and the network applications. The controller maintains up-to-date network state information about the network devices and elements (for example, hosts, switches, links) and provides it to the network-control applications. This information, in turn, is used by the applications to monitor and control the network devices.

- A programmable network: The network-control applications act as the “brain” of SDN control plane by managing the network. Example applications can include network management, traffic engineering, security, automation, analytics, etc. For example, we can have an application that determines the end-to-end path between sources and destinations in the network using Dijkstra’s algorithm.

Controller Architecture

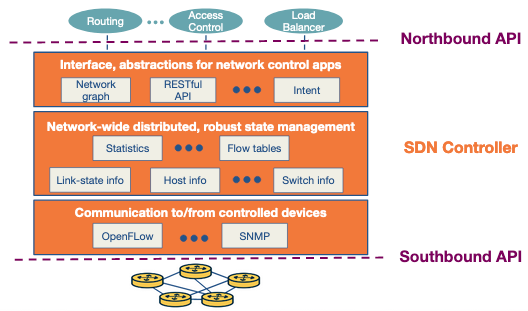

The controller itself is broken down into a further 3 layers. These handle each of its separate responsibilities.

- Communication Layer: This layer consists of a protocol through which the SDN controller and the network controlled elements communicate. Using this protocol, the devices send locally observed events to the SDN controller providing the controller with a current view of the network state. For example, these events can be a new device joining the network, heartbeat indicating the device is up, etc. The communication between SDN controller and the controlled devices is known as the “southbound” interface. OpenFlow is an example of this protocol, which is broadly used by SDN controllers today.

- Network-wide state-management layer: This layer is about the network-state that is maintained by the controller. The network-state includes any information about the state of the hosts, links, switches and other controlled elements in the network. It also includes copies of the flow tables of the switches. Network-state information is needed by the SDN control plane to configure the flow tables.

- The interface to the network-control application layer: This layer is also known as the controller’s “northbound” interface using which the SDN controller interacts with network-control applications. Network-control applications can read/write network state and flow tables in controller’s state-management layer. The SDN controller can notify applications of changes in the network state, based on the event notifications sent by the SDN-controlled devices. The applications can then take appropriate actions based on the event. A REST interface is an example of a northbound API.

The SDN controller, although viewed as a monolithic service by external devices and applications, is implemented by distributed servers to achieve fault tolerance, high availability and efficiency. Despite the issues of synchronization across servers, many modern controllers such as OpenDayLight and ONOS have solved it and prefer distributed controllers to provide highly scalable services.

Readings for part 2

Important Readings

Software-Defined Networking: A Comprehensive Survey

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1406.0440.pdfLinks to an external site.

ONOS: Towards an Open, Distributed SDN OS

https://www-cs-students.stanford.edu/~rlantz/papers/onos-hotsdn.pdf Links to an external site.

P4: Programming Protocol-Independent Packet Processors

https://www.sigcomm.org/sites/default/files/ccr/papers/2014/July/0000000-0000004.pdfLinks to an external site.

A Software-Defined Internet Exchange

https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/2740070.2626300?download=trueLinks to an external site.

Optional Readings

P4 Language tutorial

https://github.com/p4lang/tutorials/tree/master/exercises/basicLinks to an external site.

An Industrial-Scale Software Defined Internet Exchange Point

https://www.usenix.org/system/files/conference/nsdi16/nsdi16-paper-gupta.pdfLinks to an external site.

As you go through this lesson, there will be links for optional tutorials on various SDN technologies.

Advantages of SDNs

- Shared abstractions: These middlebox services (or network functionalities) can be programmed easily now that the abstractions provided by the control platform and network programming languages can be shared.

- Consistency of same network information: All network applications have the same global network information view, leading to consistent policy decisions while reusing control plane modules

- Locality of functionality placement: Previously, the location of middleboxes was a strategic decision and big constraint. However, in this model, the middlebox applications can take actions from anywhere in the network.

- Simpler integration: Integrations of networking applications are smoother. For example, load balancing and routing applications can be combined sequentially.

SND features

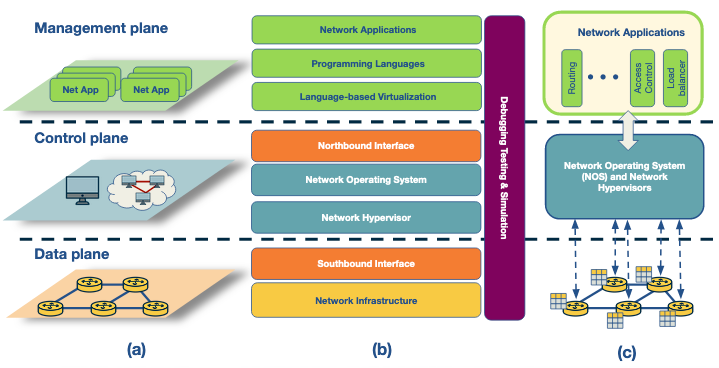

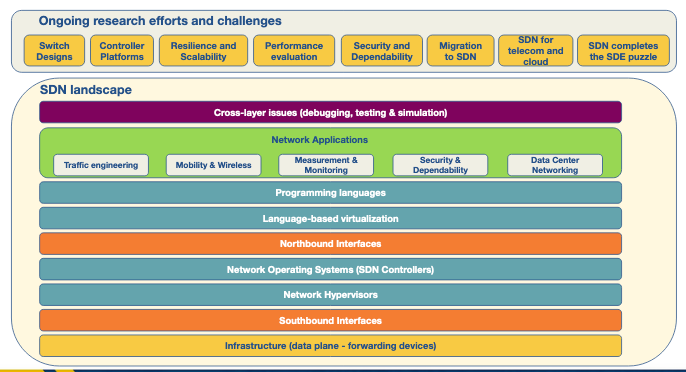

The figure below presents three perspectives of the SDN landscape: (a) a plane-oriented view, (b) the SDN layers, and (c) a system design perspective.

Next we highlight the key features of an SDN.

- Infrastructure:

- Networking equipment (e.g., routers, switches) now act as simple forwarding elements controlled by a centralized system.

- Examples: OpenFlow switches like SwitchLight, Open vSwitch, Pica8.

- OpenFlow Documentation

- Southbound Interfaces:

- Connect control and forwarding elements, enabling the separation of control and data planes.

- Popular APIs: OpenFlow, ForCES, OVSDB, POF, OpFlex, OpenStack.

- OVSDB Tutorial

- Network Virtualization:

- Supports arbitrary network topologies and addressing schemes.

- Traditional technologies: VLAN, NAT, MPLS.

- Advanced SDN technologies: VxLAN, NVGRE, FlowVisor, FlowN, NVP.

- Network Operating Systems (NOS):

- Centralized controllers that simplify network management and foster innovation.

- Examples: OpenDayLight, OpenContrail, Onix, Beacon, HP VAN SDN.

- OpenDayLight Tutorial

- Northbound Interfaces:

- Enable software ecosystems and provide abstraction from low-level details.

- Examples: Floodlight, Trema, NOX, Onix, SFNet.

- Floodlight Tutorial

- Language-Based Virtualization:

- Express modularity and abstraction in network views.

- Examples: Pyretic, libNetVirt, AutoSlice, RadioVisor, OpenVirteX.

- Network Programming Languages:

- High-level languages for modular, reusable, and faster development.

- Examples: Pyretic, Frenetic, Merlin, Nettle, Procera, FML.

- Frenetic Tutorial

- Pyretic Tutorial

- Network Applications:

- Implement control plane logic and manage data plane commands.

- Use cases: routing, load balancing, security, QoS, power reduction, virtualization, mobility management.

- Examples: Hedera, Aster*x, OSP, OpenQoS, Pronto, Plug-N-Serve, SIMPLE, FAMS, FlowSense, OpenTCP, NetGraph, FortNOX, FlowNAC, VAVE.

SDN infrastructure layer

This is the network-controlled devices. These are built on top of open standard interfaces that ensure cross-compatibility between vendors.

In OpenFlow how they handle packets is based on a flow table which has 3 entries

- A matching rule

- An action for any matching packet, and

- Counters for statistics. Potential actions could be:

- Forward the packet to outgoing port

- Encapsulate the packet and forward it to controller

- Drop the packet

- Send the packet to normal processing pipeline

- Send the packet to next flow table Once a packet matches with one rule it is normally executed meaning order matters.

South-bound interface

OpenFlow is the most widely used API for the south-bound interface. As the release cycle for most new switches is around 2 years the predominance of OpenFlow is likely to stay.

OpenFlow allows for 3 information sources:

- Event-based messages that are sent by forwarding devices to the controller when there is a link or port change

- Flow statistics are generated by forwarding devices and collected by the controller

- Packet messages are sent by forwarding devices to the controller when they do not know what to do with a new incoming flow These all communicate with the SDN controller.

There are alternatives to OpenFlow such as ForCES which provides mo flexible approach to traditional networking without changing infrastructure.

Centralised vs decentralised controllers

Essential Functions

- Topology Management: Understanding and managing the network layout.

- Statistics Collection: Gathering network data for analysis.

- Notifications: Alerting systems of events or changes in the network.

- Device Management: Overseeing the network hardware and software components.

- Shortest Path Forwarding: Determining the most efficient routes for data.

- Security Mechanisms: Ensuring isolation and enforcing security rules, prioritising high-priority services over lower-priority applications.

Controller Architectures

-

Centralized Controllers:

- Characteristics:

- Single entity managing all network devices.

- Potential single point of failure.

- Scalability issues in large networks.

- Examples:

- Maestro, Beacon, NOX-MT: Utilise multi-threaded designs to leverage multi-core processors, e.g., Beacon handles over 12 million flows per second using large computing nodes.

- Trema, Ryu NOS: Target specific environments like data centres and cloud infrastructure.

- Rosemary: Ensures security and isolation using a container-based micro-NOS architecture.

- Characteristics:

-

Distributed Controllers:

- Characteristics:

- Scalable to various network sizes.

- Can be centralised clusters or physically distributed elements.

- Suitable for large, WAN-connected data centres using a hybrid approach (clusters within data centres, distributed nodes across sites).

- Properties:

- Weak Consistency Semantics: Less strict data consistency requirements.

- Fault Tolerance: Better resilience to failures.

- Characteristics:

Example distributed controller

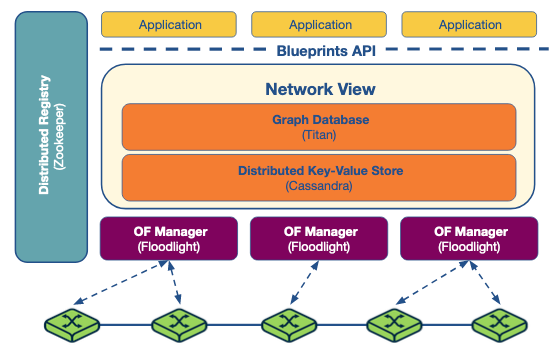

Here we will review the ONOS distributed SDN control platform. This is based on Floodlight an open-source single instance SDN controller.

Architecture:

- Cluster Setup: Multiple ONOS instances running in a cluster.

- Global Network View: Built from network topology and state information (ports, links, hosts).

- Decision Making: Applications use the global view for forwarding and policy decisions, updating the view accordingly.

- Components:

- Titan (Graph Database): Stores the global view.

- Cassandra (Distributed Key-Value Store): Manages data.

- Blueprints Graph API: Interface for applications to interact with the network view.

Performance and Fault Tolerance:

- Scale-Out Performance: Add more instances to the cluster to handle increased demand.

- Mastership: Each ONOS instance is the master controller for a group of switches, handling state changes between its switches and the network view.

- Failure Handling:

- Redistribution: Workload of a failed instance is redistributed among remaining instances.

- Master Election: New masters are elected for affected switches, ensuring each switch has one master.

- Zookeeper: Manages mastership between switches and controllers.

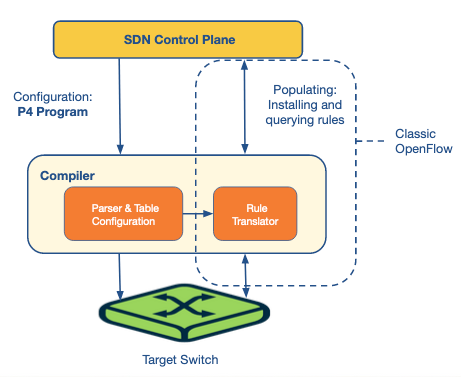

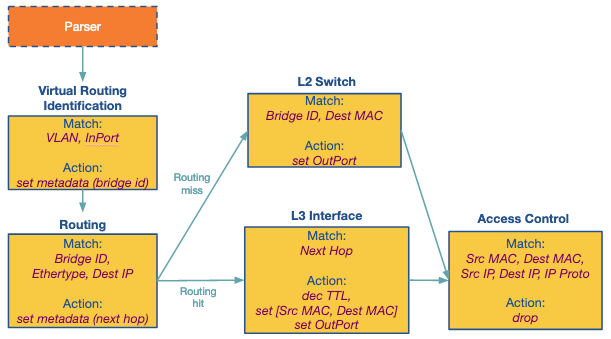

Programming languages for the control plane P4

- Purpose: A high-level programming language designed to configure network switches, complementing SDN control protocols.

- Context: Developed to address the limitations of the OpenFlow interface, which started with simple rule tables and has grown more complex to handle multiple stages and numerous header fields.

Need for P4:

- Flexibility and Extensibility: Required to parse packets and match header fields efficiently while providing an open interface for controllers.

- Controller-Switch Interaction: P4 enables controllers to define switch operations programmatically, acting as a general interface between switches and controllers.

Primary Goals of P4:

- Reconfigurability: Controllers should be able to modify packet parsing and processing within switches.

- Protocol Independence: Switches should be independent of specific protocols. Controllers define packet parsers and match-action tables for processing.

- Target Independence: Packet processing programs should be independent of the underlying hardware. P4 programs are compiled into target-specific configurations to program switches.

P4 enhances switch programmability, ensuring they can adapt to various protocols and hardware environments while providing a flexible and open interface for SDN controllers.

This operates within the switch in two steps:

- Configure: These sets of operations are used to program the parser. They specify the header fields to be processed in each match+action stage and also define the order of these stages.

- Populate: The entries in the match+action tables specified during configuration may be altered using the populate operations. It allows addition and deletion of the entries in the tables.

Below is an example dependency graph for the P4 language.

SDN Applications

-

Traffic Engineering:

- Focus: Optimize traffic flow to minimize power consumption, use network resources efficiently, and perform load balancing.

- Techniques: Use optimization algorithms and monitor data plane load via southbound interfaces.

- Examples:

- ElasticTree: Shuts down specific links and devices based on traffic load.

- Load Balancers (Plug-n-Serve, Aster*x): Create rules based on wildcard patterns for scalability.

- ALTO VPN: Enables dynamic VPN provisioning in cloud infrastructures.

-

Mobility and Wireless:

- Challenges: Manage limited spectrum, allocate radio resources, and perform load balancing.

- SDN Benefits: Simplifies deployment and management of wireless networks (e.g., WLANs, cellular networks).

- Features: On-demand virtual access points (VAPs), dynamic spectrum usage, shared wireless infrastructure.

- Examples:

- OpenRadio: Provides an abstraction layer, decoupling wireless protocols from hardware.

- Light Virtual Access Points (LVAPs): Map one-to-one with clients for better management.

- Odin Framework: Uses LVAPs for mobility management and channel selection, allowing seamless movement between access points.

-

Measurement and Monitoring:

- Goals: Add new features and improve existing SDN features using OpenFlow.

- Methods: Reduce control plane load from data collection using sampling and estimation techniques.

- Examples:

- OpenSketch: Offers flexibility for network measurements.

- Monitoring Frameworks (OpenSample, PayLess): Enhance monitoring capabilities.

-

Security and Dependability:

- Focus: Enhance network security through programmable devices and policies.

- Approaches: Impose security policies at network entry points and throughout the network.

- Examples:

- DDoS Detection: Identifies and mitigates DDoS attacks using network information.

- OF-RHM: Randomly mutates IP addresses to fake dynamic IPs for attackers.

- CloudWatcher: Monitors cloud infrastructures.

- SDN Security Improvements: Include rule prioritisation and ongoing research for better security measures.

-

Data Center Networking:

- Benefits: Revolutionize data center operations with services like live network migration, troubleshooting, and real-time monitoring.

- Features: Detect anomalous behaviour, dynamic reconfigurations during live migrations.

- Examples:

- LIME: Provides live migration capabilities.

- FlowDiff: Detects abnormalities in data center networks.

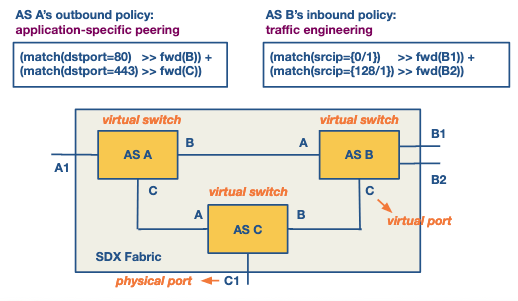

SDX

Routing using BGP has some serious limitations:

- Routing only uses destination IP: We want customisation based in the traffic application or source IP.

- Little control over end-to-end paths: We can only speak to our neighbours or look at the as-path field. These could be addressed using SDN.

This has been implemented in IXPs using SDX. This allows for:

- Application specific peering - Custom peering rules can be installed for certain applications, such as high-bandwidth video applications like Netflix or YouTube which constitute a significant amount of traffic volume.

- Traffic engineering - Controlling the inbound traffic based on source IP or port numbers by setting forwarding rules.

- Traffic load balancing - The destination IP address can be rewritten based on any field in the packet header to balance the load.

- Traffic redirection through middleboxes - Targeted subsets of traffic can be redirected to middleboxes.

At an IXP each participant connects to the route server - there they get a virtual sdn switch where they decide the in/outbound rules for traffic leaving and entering their network. These do not effect other participants switches but does effect how traffic is routed through the IXP. This differs from a standard route server which uses BGP rules to control traffic form/to participant AS.

This is written in Pyretic and example can be found below.

Wide area traffic delivery

- Application-Specific Peering

- Current Challenge: ISPs need to handle high-bandwidth application traffic (e.g., YouTube, Netflix) with dedicated ASes and configure additional rules in edge routers.

- SDX Solution: Custom rules can be configured at the SDX to identify and direct specific application traffic, eliminating the overhead on ISP edge routers.

- Inbound Traffic Engineering

- Current Challenge: BGP routes based on destination address, with limited control over inbound traffic through AS path prepending and selective advertisements, which can pollute global routing tables.

- SDX Solution: An SDN-enabled switch can install forwarding rules based on source IP and port, allowing ASes to control inbound traffic more effectively than with BGP.u

- Wide-Area Server Load Balancing

- Current Challenge: Traditional DNS-based load balancing can lead to slower responses due to DNS caching and inefficiencies during failures.

- SDX Solution: With SDX, packet headers can be modified to direct traffic to the appropriate backend server using a single anycast IP, improving load balancing efficiency.

- Redirection Through Middleboxes

- Current Challenge: Placing middleboxes at every necessary junction is costly for large ISPs, and routing protocols like iBGP to redirect traffic can be inefficient.

- SDX Solution: SDX can dynamically identify and redirect traffic through a sequence of middleboxes, optimizing middlebox usage without unnecessary traffic redirection.

Key Advantages

- Customization: Each AS can tailor its traffic policies without affecting others.

- Efficiency: SDX enables more precise traffic control and management, reducing overhead and inefficiencies.

- Scalability: SDX’s ability to manage and combine policies ensures scalable and flexible network operations.

These use cases demonstrate how SDX architecture can enhance traffic management, load balancing, and the use of middleboxes, providing a more efficient and flexible network infrastructure.

/../../images/sdn_planes.png)