Week 5 - Router design and algorithms

Part 1

Additional reading

Important Readings

Survey and Taxonomy of IP Address Lookup Algorithms

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/71d9/018e900f99ff60653b3769160131e775873f.pdfLinks to an external site.

Book References

Kurose-Ross, 6th Edition, Section 4.3

Kurose-Ross, 7th Edition, Section 4.2

Varghese, Network Algorithmics, Sections: 1.1.2, 2.3.2, Chapter 11

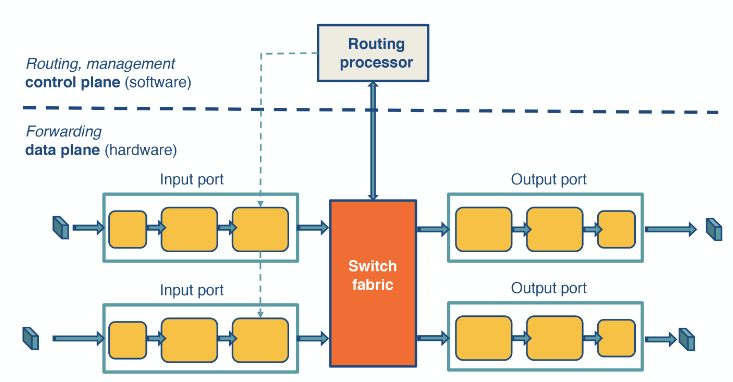

What is inside a router

There are two parts of a router.

- The forwarding plane, and

- The Control plane.

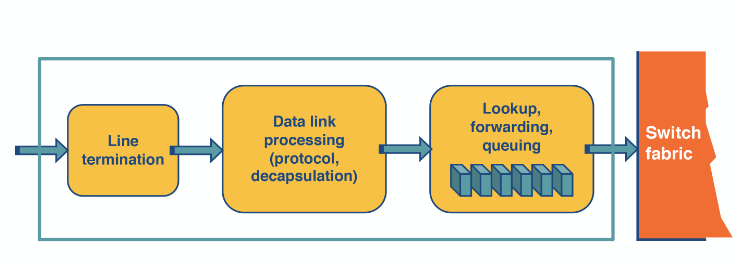

The forwarding plane is responsible for getting messages forwarded when they arrive at the router. Which has 3 main components:

- Input queue: responsible for finishing the layer 1 process and de-encapsulation the message to get the IP address. The it looks up where it has to go and moves it onto the switching fabric.

- Switching fabric: Only responsible for getting messages from the input queue to the correct output queue.

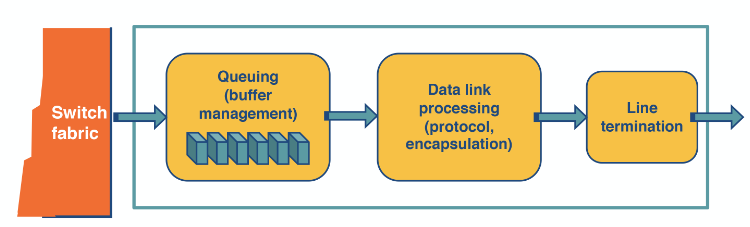

- Output queue: The same as the input but backwards.

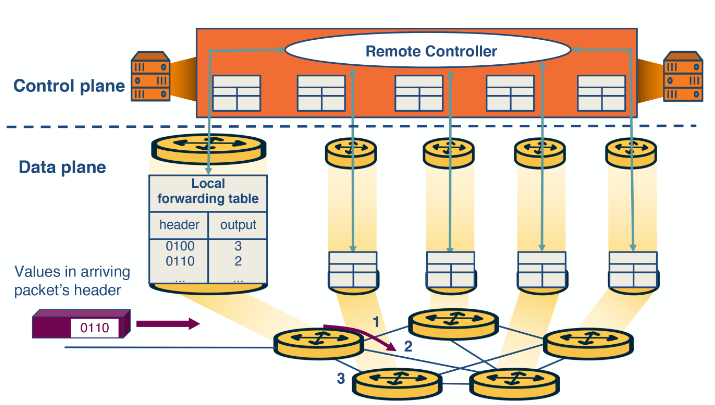

The control plane refers to the implementation of the router protocols. This mainly involves keeping the forwarding table up to date.

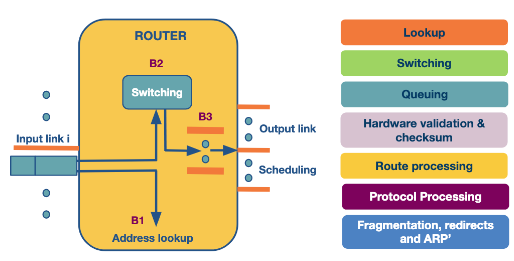

Router architecture

Here we depict what happens when a packet arrives at the router.

The most time sensitive operations are lookup, switching and scheduling.

- Lookup: When a packet arrives this uses the IP address to find the output link in the Forwarding information base (FIB). It uses longest prefix matching to do this. Some routers offer more complicated lookups using ports and other criteria.

- Switching: This involves moving from the input link to the output link. Modern routers will use crossbar switching. Though scheduling this can be complicated if multiple inputs want to go to the same output.

- Queuing: This is exactly what it sounds like. Some routers use a FIFO queue but they can deploy more complicated weighted queues to implement delay guarantees or fair bandwidth allocation.

- Header validation and checksum: Check the packet, update TTL and recalculate the checksum.

- Route processing: Building the Forwarding information base (FIB). This uses protocols such as RIP, or OSPF.

- Protocol processing: The routers need to implement: SNMP, TCP, UDP, and ICMP for sending error messages.

Switching fabric

This can be accomplished in one of 3 ways.

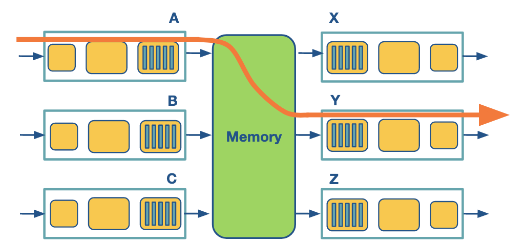

Via Memory

Input/Output ports operate as I/O devices in an operating system, controlled by the routing processor. When an input port receives a packet, it sends an interrupt to the routing processor, and the packet is copied to the processor’s memory. Then the processor extracts the destination address and looks into the forward table to find the output port, and finally, the packet is copied into that output’s port buffer.

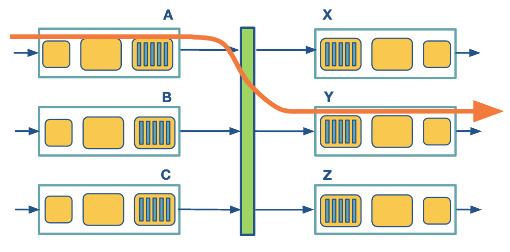

Via bus

In this case, the routing processor does not intervene as we saw the switching via memory. When an input port receives a new packet, it puts an internal header that designates the output port, and it sends the packet to the shared bus. Then all the output ports will receive the packet, but only the designated one will keep it. When the packet arrives at the designated output port, the internal header is removed from the packet. Only one packet can cross the bus at a given time, so the speed of the bus limits the speed of the router.

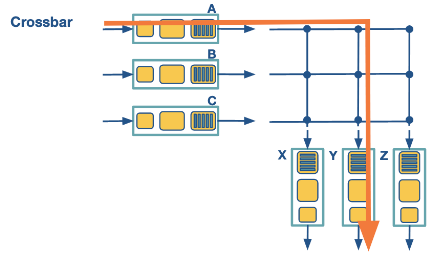

Via interconnected network (crossbar)

A crossbar switch is an interconnection network that connects

Problems facing routers

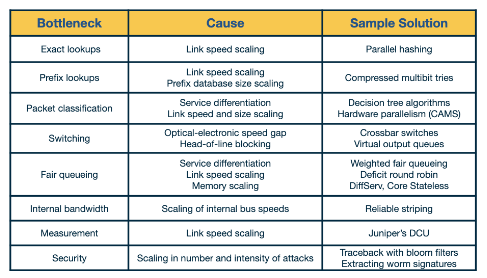

Modern routing facing a lot of problems when handling the scale of the internet.

- Bandwidth and Internet Population scaling: These are caused by

- Increased number of devices connected to the internet.

- Increasing volumes of network traffic.

- New devices that can operate at high speeds.

- Services at high speeds: New devices that need to operate at high speeds which can be effected by congestion or attacks on the network.

Longest prefix matching Matching a packet to the FIB can be complicated. New routers offer more complicated lookups as well.

Service differentiation This allows routers to offer per service guarantees such as delay insurance and fairness within services. This requires the router to inspect packets deeper than it otherwise would.

Switching limitation Moving packets from the input to output link has some hard limitations to it as we will see with head of line blocking.

Bottlenecks about services Providing performance guarantees at high speed such as measurements and security.

Prefix-match Lookups

Matching addresses to entries in the FIB is one of the most time sensitive and mathematically hard operations in a router.

Prefix notation

Here we denote prefixes in 3 ways.

- Wildcard: Here we just write the prefix of the address and then use a * to denote the end of the prefix.

- Slash notation: We provide the IP address followed by a slash and the size of the relevant prefix in bits. i.e. 123.0.0.0/8.

- Masking: We provide the IP address with the network mask.

Variable length prefixes

In the early days of the Internet there were fixed length prefixes. Though this drove the problem that we are running out of IPv4 addresses on the pubic internet.

Better lookup algorithms

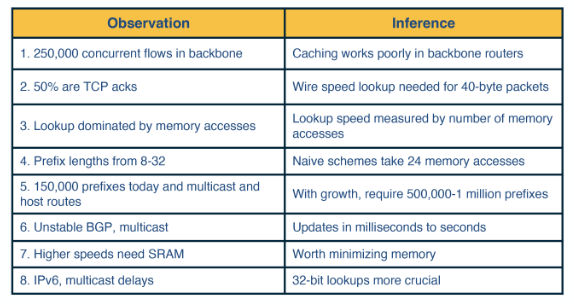

There are many problems that just the lookup process faces.

- Measurement studies on network traffic had shown a large number (in the order of hundreds of thousands - 250,000 according to a measurement study in the earlier days of the Internet) of concurrent flows of short duration. This already large number has only been increasing, and as a consequence, caching solutions will not work efficiently.

- The important element of any lookup operation is how fast it is done (lookup speed). A large part of the cost of computation for lookup is accessing memory.

- An unstable routing protocol may adversely impact the update time in the table: add, delete or replace a prefix. Inefficient routing protocols increase this value up to additional milliseconds.

- A vital trade-off is memory usage. We can use expensive fast memory (cache in software, SRAM in hardware) or cheaper but slower memory (e.g., DRAM, SDRAM).

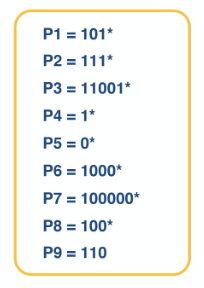

Unibit Tries

Trie

Link to originalTrie

A trie or prefix tree is used for associating words in a given alphabet

to some values in .

- This is given by a directed rooted tree

. - An edge letter map

, where . - A node key map

where is a null value. Then every word

in has a path in where and . Then either or has no edge labelled . We then can use this to associate a value to it is the last non-null value in the sequence or it is null.

We can use subnet to form a trie over the alphabet of

Prefix-match lookup

Then we use this trie as the description entails.

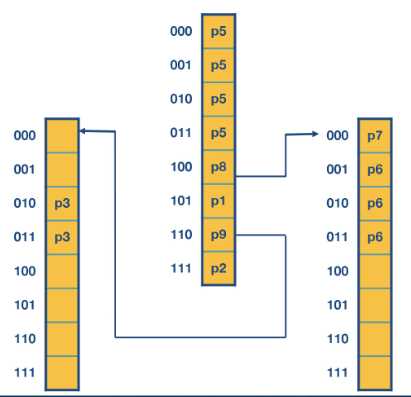

Multibit tries

Whilst unibit tries is very efficient in terms of space they can be slow in terms of memory lookups. For a substring of length

We have two approaches here.

- Fix stride length

generating children. - Variable length stride depending on the number of children, like P9 above.

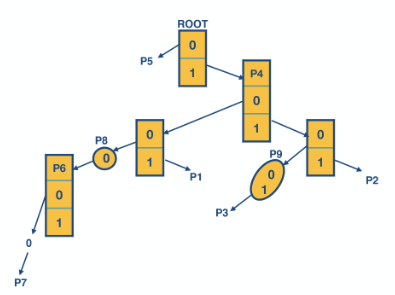

Fixed length multibit tries

Here we pick a length of stride

Prefix expansion

Suppose we set

then using the table from the previous example lets do prefix expansion.

Then we construct the multibit trie the same way as the unibit trie with the expanded addresses but with the alphabet set to bit strings of length

Notice here we only needed to have at most 3 lookups whereas before it was 5.

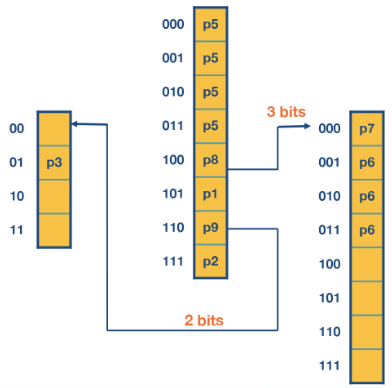

Variable length multibit tries

In the previous example we can see by choosing length 3 words the table to the left is much larger than we needed it to be. P3 was only length 2 and we had no other entries in that table. This wastes space - so we can let the length of that string be 2 instead.

The optimal stride length can be chosen using dynamic programming. Though they do not say how.

Part 2

Additional readings

Book References

Varghese, Network Algorithmics, Chapters 12, 13, 14

Kurose-Ross, 6th Edition, Section 7.5.2

Kurose-Ross, 7th Edition, Section 9.5.2

Packet classification

To guarantee more features within a router such as quality of service, security and protocol based handling of packets we need to classify packets on more than just their destination IP.

These further classifications can be based on source IP address, TCP flags, ect. We refer to this as packet classification. This is deployed by many applications such as:

- Firewalls,

- Resource reservation protocols, and

- Routing based on traffic type.

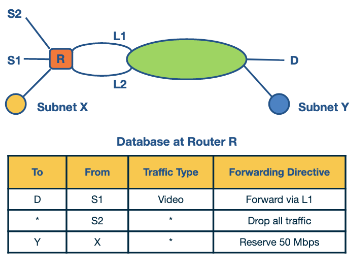

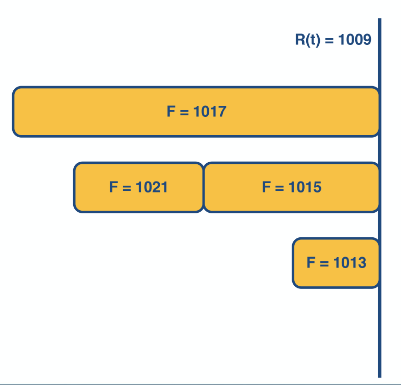

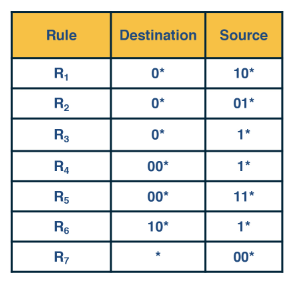

Example for traffic type sensitive routing. The above figure shows an example topology where networks are connected through router R. Destinations are shown as S1, S2, X, Y, and D. L1 and L2 denote specific connection points for router R. The table shows some examples of packet classification rules. The first rule is for routing video traffic from S1 to D via L1. The second rule drops all traffic from S2, for example, in the scenario that S2 was an experimental site. Finally, the third rule reserves 50 Mbps of traffic from prefix X to prefix Y, which is an example of a rule for resource reservation.

Simple solutions

Linear search

Firewalls do a linear search through a rules table like above and keep track of the best match. This is fine for a small number of rules but scales linearly in the number of rules.

Caching

If you are going to get a lot of similar packets then caching could be used on top of another search algorithm. This has two problems

- The cache-hit rate can be high (80-90%) but still need to perform searches on the misses,

- If the underlying search like linear has poor performance this can still have low overall performance.

Passing labels

This involves the sender attaching labels to the header that determine when happens to it. This means that intermediary routers do not need to reclassify packets on a path to the destination. Though this will require security to ensure bad actors can not abuse this. This is deployed in Multiprotocol label switching (MPLS) and DiffServ.

More tries

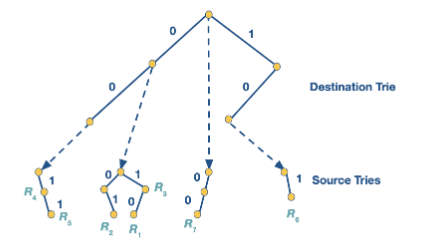

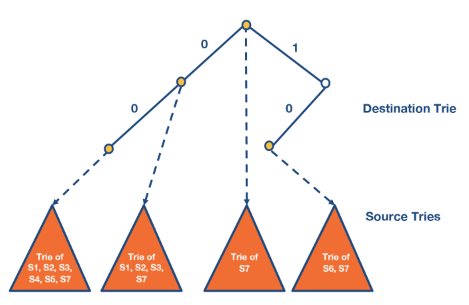

Assume we are in a position where we need to use the destination and source IP address to determine the rule. The address must match both the subnets and ties are broken first by the longest matching destination subnet then by the longest matching source subnet.

A simple way to do this would be to construct the destination trie then at the leaf nodes attach source tries.

Set-Pruning tries

The need to match all rules that could fit with the prefix means we have to repeat the same rule in multiple branches. This leads to a memory explosion in large examples.

This prefers the longest matching source subnet

This can be mitigated by switching the order of source and destination when constructing the trie.

Backtracking

We could get around the memory problem by letting each rule only appear in one source trie. Then if you don’t match in current source trie you backtrack on the destination trie and go to the next source trie. In the example above we get the following trie.

Whilst this reduces memory the downside to this approach is the time to compute the answer. If a packet has lots of backtracking you have lots of memory lookups which is slow.

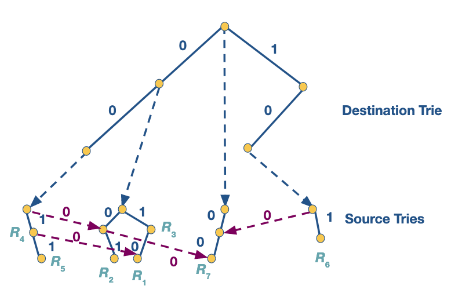

Grid of tries

We can get the best of both worlds if we precompute where the misses land in the backtracked trie. This means we don’t need to recalculate the source path we had already walked. In the example above we would get the following.

Scheduling and head of line blocking

Scheduling

Assume we have an

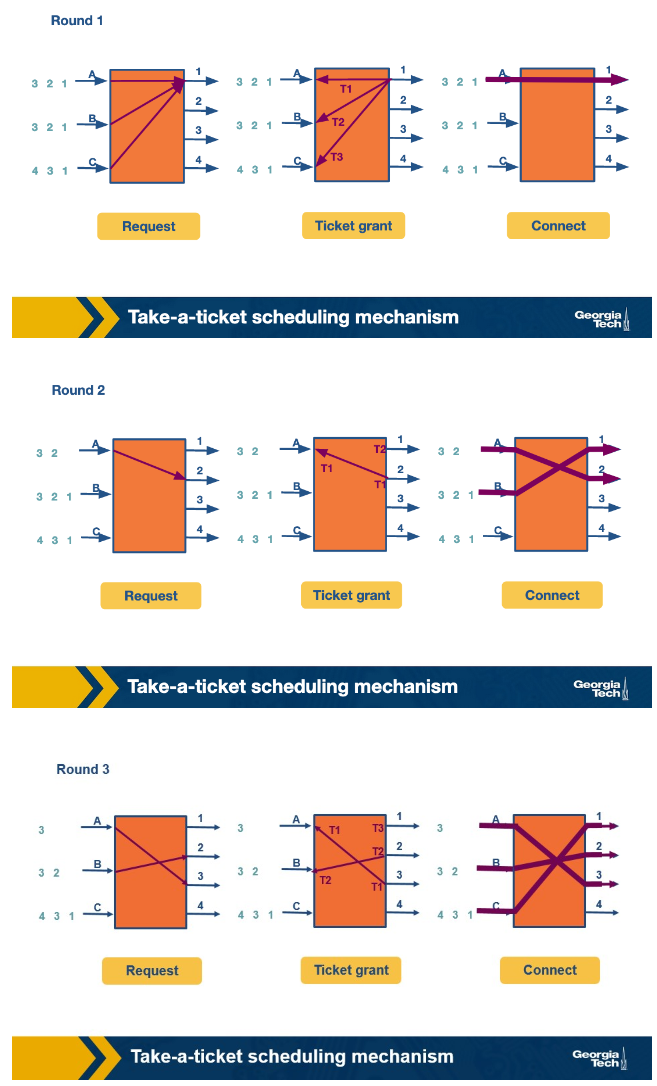

Take-a-ticket algorithm

This is analogise to input lines taking a ticket to wait to be served by a given output line. The output lines serve the requests in order. This has rounds that follow the pattern.

- Input ques make requests to output ques to send a message if needed.

- The output queues grant tickets to the input queues.

- The holder of the latest ticket for each output queue connects and passes its transaction on.

However this algorithm has a clear problem if all the inputs want to connect to the same output.

Head of line (HOL) blocking

Link to originalHead of line (HOL) blocking

In the switching fabric, head of line blocking happens when all inputs want to connect to the same output line. Then each of the queues are blocked whilst these requests get served. This can slow down switching fabric especially if inputs also have messages for other outputs that could get served.

If we can avoid HOL blocking we achieve a big speedup. In the example above we could do the same message passing but in only 3 iterations. Though for this we sacrifice “fairness”.

Knockout scheme

This uses output queuing to get around HOL blocking. If our switching fabric operates

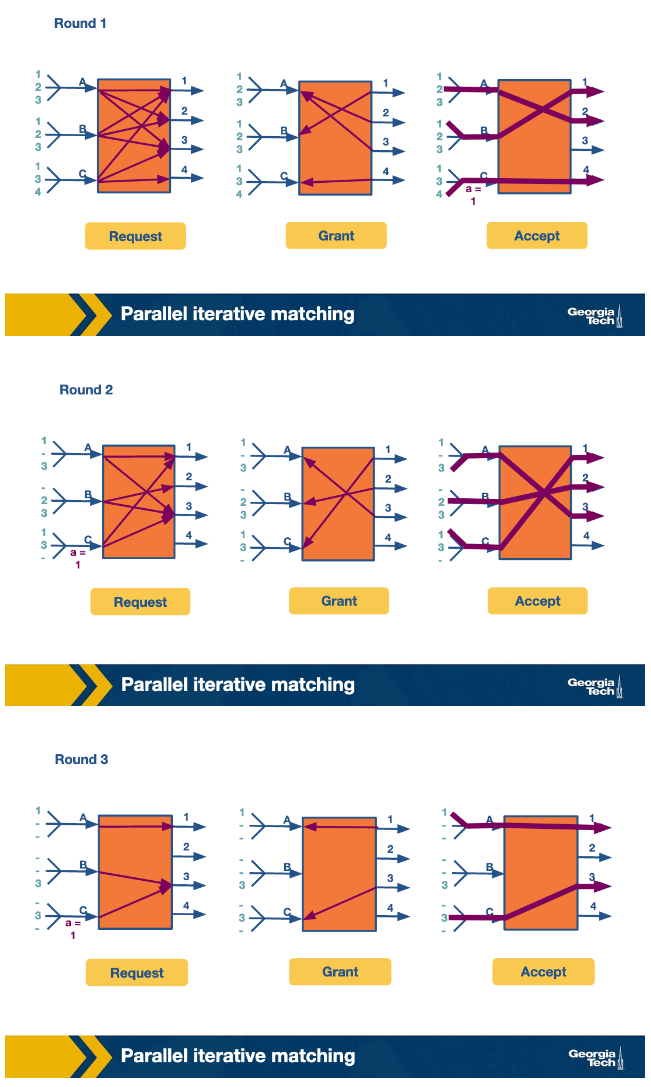

Parallel iterative matching

Here we let input lines request access for each output line they have a packet for. This goes as follows:

- Input lines request a route for each output lines they have a packet for.

- Output lines randomly select an input line to complete a transaction with.

- If an input line has more than one offer it randomly selects a transaction to complete.

- Connection happens.

Custom Scheduling

Scheduling can allow different types of packets to get different services. This is done in real time so will need to be done at inter packet times.

FIFO with tail drop

Traditional schedule approach. Each input link is a FIFO queue where if the queue is full any new additions get dropped.

Need for Quality of Service (QoS)

If you have some QoS guarantees such as maximum delay or a given bandwidth you employ smarter scheduling techniques. Here it is useful to think of network flows - packets that are all following the same route from source to destination. This flow will need to be recognisable from a header.

In the following examples you might want to make smarter routing decisions:

- Router support for congestion.

- Providing QoS guarantees to flows.

- Fair sharing of links among competing flows.

Round Robin

This is a method to control bandwidth reservations in schedulers for multiple flows.

Bit-by-bit round robin

If we could split packets into bits we could employ absolute fairness by switching from flow to flow delivering each bit. This is a round robin.

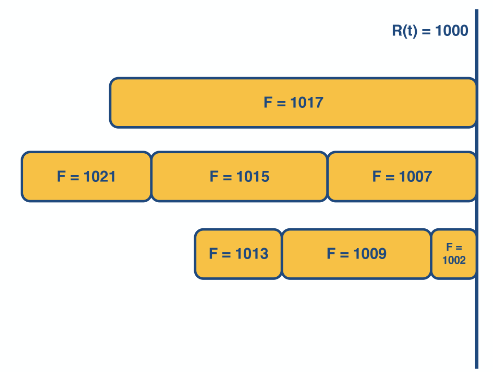

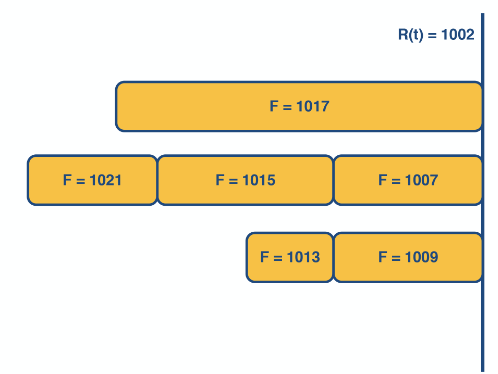

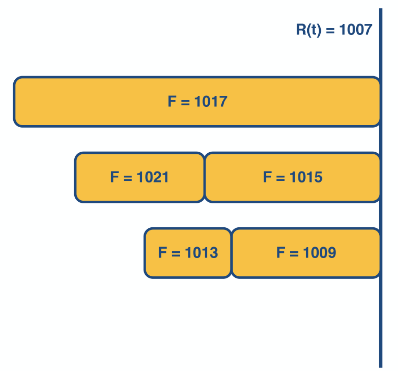

We can not split packets up so we will simulate this by making a “round number” delivering packets based on this value assigned to each request.

Let

For the

Though when do we send packets using this scheme?

Packet-level fair queueing

This is a method that uses bit-by-bit round robin framework to make fair queues.

It achieves this by sending the packet that has the smallest finish time

Whilst this guarantees fairness keeping track of all the finishing time would require a propitiatory queue method which has time complexity of

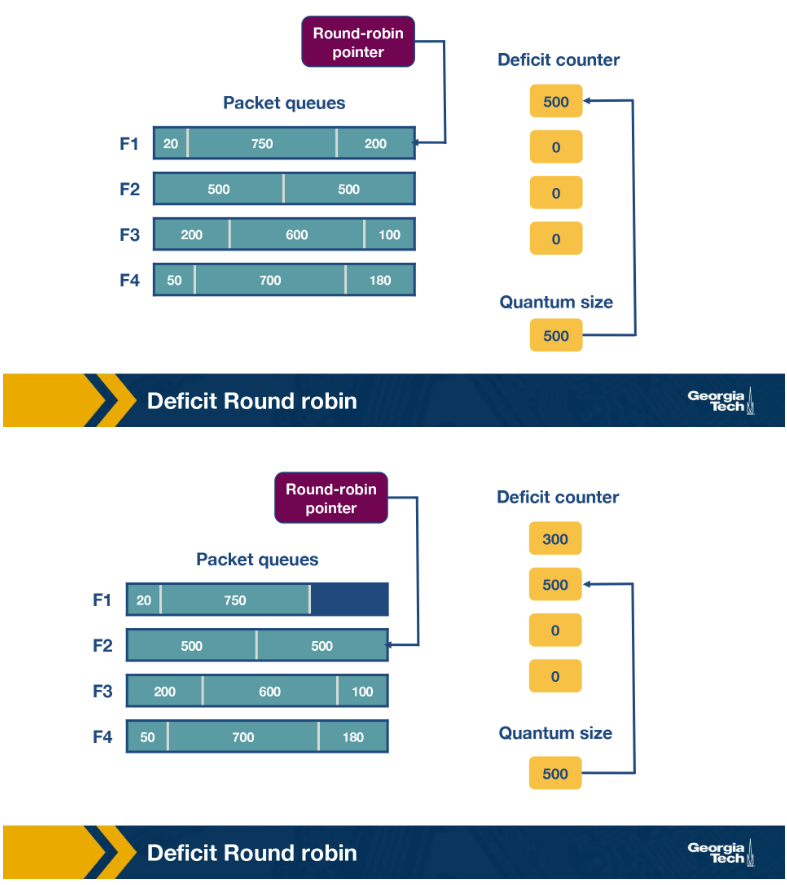

Deficit Round Robin (DRR)

Whilst the bit-by-bit round robin was completely fair and ensured bandwidth and delay guarantees the time complexity made it infeasible.

Instead we can use round robin to given each flow some allocation to use for packets. If the next packet size is less than their current allowance we send it reducing their allowance by that size. For this we set some quantum size for each flow

1. Loop forever

2. for each flow i

1. Increment D(i) += Q_i

2. While there is a next packet of size p such that p < D(i):

1. Decremet D(i) -= p

2. Send p

Deficit Round robin has one fail condition. If a flow has not had any packets for a while it allowance may build up which then could release a burst of packets. This might not be desirable if you want to guarantee a constant rate to other flows.

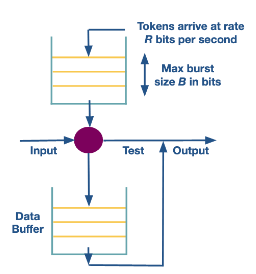

Token bucket

Token bucket shaping is similar to Deficit round robin but here we limit the number of tokens in the counter by

- limiting the average rate, and

- limiting the maximum burst size.

If a packet arrives and the bucket does not have enough tokens we have two options:

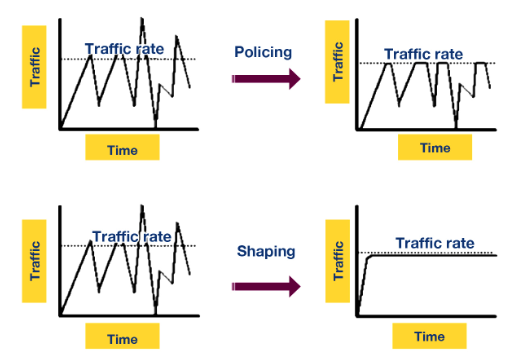

- Put it into a buffer and wait for that bucket to have enough tokens, this is traditional token bucket shaping, or

- Drop the packet, this is called bucket policing.

This leads to very different traffic throughput on the router.

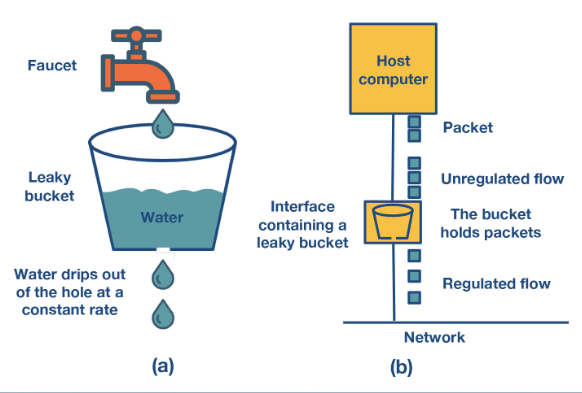

Leaky bucket

There is a middle ground between policing and shaping that combines the benefits of both. Instead of having tokens added to the bucket instead think of it being the packets we need to send. If there is room in the bucket we add the packet to the buffer and wait to send it. If the packet is too big to fit in the bucket we discard it. We then send packets at a constant rate in terms of size - thus the leak.

This can take a irregular flow and regularise it. This has the benefit of having a controlled size of buffer which can offset overflow.

then we use these strings to construct the following

then we use these strings to construct the following  we do not include the left branch of this

we do not include the left branch of this

Then we attach the following

Then we attach the following  Note that for the 00* source trie we need to include all rules that could match that prefix in particular even rules that only match the 0*.

Note that for the 00* source trie we need to include all rules that could match that prefix in particular even rules that only match the 0*.-blocking/../../images/head_of_line_blocking.png)