Week 10 - Synchronization Constructs

Additional reading

Synchronization

Synchronization

Link to originalSynchronization

Synchronization is the processes by which two or more independent operators coordinate with one another to manage shared resources or coordinate work with one another.

Previously we discussed mutexes and conditional variables. However these had a couple of downsides:

- Error prone usage.

- Lack of expressive power. These also needed low level support via atomic instructions.

Atomic instruction

Link to originalAtomic instruction

An atomic instruction in computer systems is an operation that is indivisible — it either completes entirely or does not happen at all, with no intermediate state visible to other threads or processors. Atomicity is crucial in concurrent programming to avoid race condition when multiple threads access and modify shared data.

There are different synchronization constructs we will look at.

Spinlocks

Link to originalSpinlocks

Spinlocks are a synchronization construct that are similar to mutexes. When a processes tries to acquire the lock whilst another process has it - it will wait at the unlock operation. However, in comparison to a mutex the spinlock will not relinquish the CPU instead choosing to keep checking if the lock has become free.

Semaphores

Link to originalSemaphores

Semaphores are a synchronization construct used to control access to shared resources. A semaphore is initialized with an integer value (often called the capacity). It maintains a counter that represents the number of available “permits.” When a thread attempts to acquire the semaphore:

- If the counter is greater than 0, the thread decrements it and proceeds.

- If the counter is 0, the thread blocks (waits) until another thread releases the semaphore.

When a thread releases the semaphore, the counter is incremented by 1, potentially waking a waiting thread.

This mechanism ensures that at most the initial number of threads (the max count) can hold the semaphore concurrently.

Reader-writer locks

Reader-writer locks

A reader-writer lock is a synchronization construct that allows multiple threads to read shared data concurrently, while ensuring exclusive access for a thread that needs to write. It supports two types of locking:

Link to original

- Read lock: Multiple threads can acquire the read lock simultaneously, as long as no thread holds the write lock.

- Write lock: Only one thread can hold the write lock at a time, and no other thread (reader or writer) may hold the lock concurrently.

Reader-writer locks typically expose two distinct interfaces — one for acquiring and releasing the read lock, and one for the write lock — with internal coordination to ensure mutual exclusion between readers and writers when necessary.

Monitors

Link to originalMonitors

Monitors are a high-level synchronization construct that encapsulate:

- A shared resource,

- A set of mutexes (or equivalent) to enforce mutual exclusion, and

- One or more conditional variables used for managing waiting and signaling between threads.

A monitor typically exposes an API consisting of entry procedures (methods), and ensures that:

- Entering threads abide by the prescribed entry conditions,

- Threads can wait on a condition (e.g. “buffer not empty”), releasing the lock temporarily, and

- Other threads can signal those waiting threads when the condition becomes true.

The monitor takes care of locking, unlocking, waiting, and signaling internally, so the user doesn’t have to manually manage these lower-level details.

However there are many more - though they all require support from the hardware to operate. Mainly through the use of atomic instructions.

We will talk about different implementations of spinlocks in this section. Note that without hardware support you can not both check the status of the lock and change the status of the lock - therefore you can not have a safe implementation as you can not guarantee threads will not be interwoven at inopportune times.

Atomic instructions

The set of atomic instructions is different on different architectures. Some examples are:

- test_and_set: Return the current value of a variable and set it to a given value.

- read_and_increment: Return the current value of a variable and increase it by 1.

- compare_and_swap: Return true/false comparing two values and swap them. Though as these are atomic instructions the hardware guarantees the operation will be completed without being interrupted.

Test and set spinlock implementation

We can use the test_and_set operation to implement a spinlock. Suppose the lock has values 0 or 1. With 0 being free and 1 being locked.

busy = 1

free = 0

// initialise

lock = free

// lock

while(test_and_set(lock, busy) == busy);

// unlock

lock = free;Shared memory multiprocessors and caches

It is common for CPU’s to share memory and have a local cache. Depending on the architecture of the shared memory they can have a single or multiple read/write operations in flight at the same time. Also the cache may or may not be in sync with the lower level memory.

Cache coherence

Link to originalCache coherence

Cache coherence refers to the process of keeping multiple cached copies of the same memory location consistent across different caches. This is especially important in multi-core processors, where each CPU core may have its own cache.

There are two primary strategies for maintaining coherence:

- Write-invalidate: When a core writes to a cached value, it invalidates that value in all other caches. Other cores must fetch the updated value from memory (or the writing core) on their next access. This is a lazy strategy — it saves bandwidth but may cause a delay on future reads.

- Write-update: When a core writes to a cached value, it broadcasts the update to all other caches so they can update their copies immediately. This is an eager strategy — it keeps all caches ready, but increases communication cost.

CPU architectures can either be cache coherent or non-cache coherent. If they are non-cache-coherent then you will have to program this in software rather than rely on the hardware.

Atomic operations and cache coherence

For two CPU’s to act independently whilst also supporting shared atomic instructions with one another they can not cache any value that support atomic instructions. The two CPUs could not guarantee two atomic instructions did not happen at the same time.

To contend with this CPU’s will not cache atomic values - however this means memory access in this case is very slow. Therefore shared memory CPU’s have very slow atomic instructions.

Spinlock evaluation criteria

There are 3 desirable traits for a spinlock:

- Low latency: The time to acquire a free lock should be as low as possible, ideally immediately.

- Low delay: The time to stop spinning and acquire a lock that has been free to be as low as possible, ideally immediately.

- Low contention: The amount of traffic looking to access the lock should be as low as possible, ideally zero so operations viewing the lock are fast.

With these goals the first two are in direct conflict with the last one - to make lower the latency and delay we want to access the variable more thus increasing contention.

Test_and_set spinlock implementation

This implementation just spins on an atomic operation. This will have minimal delay and latency as we will immediately get new values however for this we pay with massive contention by all waiting threads updating an atomic value. This means that the releasing thread will be delayed on giving up control.

Spin on read

This uses a cached value of the lock and only when that changes tries the atomic operation.

busy = 1

free = 0

// initialise

lock = free

// lock

while(lock == busy or test_and_set(lock, busy) == busy);

// unlock

lock = free;For both latency and delay this is ok, both getting a free lock or a released lock require 1 more operation before obtaining it. However the contention depends on the system:

- Non-cache-coherent: No different to test_and_set.

- Cache-coherent with write update: Ok, as all the references are updated quickly.

- Cache-coherent with write invalidate: Worst, as they all need to get the cached value again and then try the atomic operation which invalidates all the caches again.

Delay based spin lock

This implementation introduces delay on the lock operation. The first one adds a delay after a thread realizes the lock is free.

busy = 1

free = 0

// initialise

lock = free

// lock

while(lock == busy or test_and_set(lock, busy) == busy) {

while(lock == busy);

delay();

};

// unlock

lock = free;This spreads out the threads attempts to perform the atomic operation allowing for cache to be updated and lowering contention. This keeps latency just as good as in the spin on read case as obtaining a free lock is fast. However as we are introducing a delay in the lock - this clearly makes the delay worse.

We can remove the inner while loop so it does not spin constantly but this hurts delay a lot more as threads will constantly be delayed.

How long to delay

There are two main strategies here,

- Static delay: Fixed delay based on some properties of the thread such as the CPU id.

- Dynamic delay: Random delay in a range that increases with “perceived” contention.

A static delay normally multiplies the length of the critical section by some constant in hopes to space out lock access. This is simple but may cause unnecessary delay under low contention.

Dynamic delay normally operates more efficiently but requires to use a proxy to calculate the “perceived” contention. This is normally failed test_and_set operations which puts these systems vulnerable to variations in the critical section length causing extra delay.

Queue lock

This implements a queue for each lock. This queue holds processes that are waiting on the lock.

// initialise

flags[0] = has-lock

flags[1..p-1] = must-wait

queuelast = 0; // global

// lock

myplace = read_and_increment(queuelast);

while(flags[myplace mod p] == must-wait);

flags[myplace mod p] == must-wait;

// unlock

flags[myplace+1 mod p] = has-lockWhen the lock is released the next process in the queue gets it. This has no contention as the variable we are waiting on is not the atomic. It has minimal delay as the unlocking thread directly signals the waiting thread. Though due to the more complex implementation the latency has gotten worse. However this needs

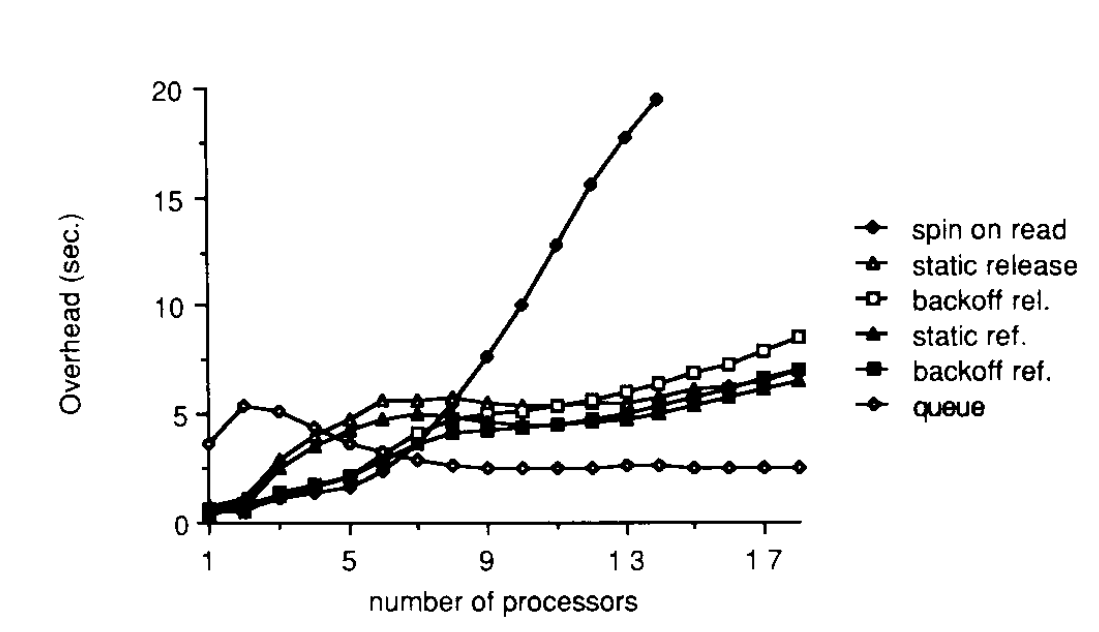

Performance comparison

Within the referenced paper they compare the performance of different spinlock implementations using different numbers of processes all repeating a critical section 1 million times. Below surmises the results.

The value provided here is the real run time minus the theoretical best run time (i.e. one with no lock required). The machine they operate on is cache coherent with write invalidate.

Under high load the queue structure performs the best, and as discussed previously the spin on read implementations high coherence causes massive delay.

Under light load though the queue implementation is terrible due to the more complex logic to implement - the cost is not amortized over multiple threads.